During slavery in America, enslaved men, women and youngsters also enjoyed the vacations. Slave owners normally gave them larger portions of food, gave them alcohol and provided them with additional days of rest.

However, these gestures weren’t made out of generosity.

As an abolitionist, orator and diplomat Frederick Douglass explained that slave owners attempted to maintain enslaved people under control by imposing higher meals and more downtime in hopes of stopping escapes and rebellions.

Most of the time it worked.

But as I describe in my most up-to-date book: “People in Bondage: An Atlantic History of Slavery“Many enslaved people were on the heels of their owners and used this transient respite to plan escapes and spark rebellions.

Feasting, romping and tinkering

Most enslaved people in America followed the Christian calendar—and celebrated Christmas—as either Catholicism or Protestantism predominated, from Birmingham, Alabama to Brazil.

Consider the instance of Solomon Northup, whose tragic story is depicted within the film “12 years a slave.” Northup was born free in upstate New York but was kidnapped and Sold into slavery in Louisiana in 1841.

In his narrative, Northup explained that his owner and his neighbors gave their slaves between three and 6 days off through the holidays. He described this time as a “carnival time with the children of bondage”, a time of “celebration, romp and play”.

According to Northup, yearly a slave owner in Bayou Boeuf in central Louisiana hosted a Christmas dinner attended by as much as 500 enslaved people from neighboring plantations. After eating meager meals all yr, this was a rare opportunity to bask in various kinds of meat, vegetables, fruits, cakes and pies.

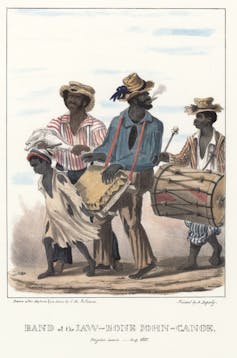

Images of slavery

There is evidence of holiday celebrations for the reason that early days of slavery in America. In the British colony of Jamaica a Christmas masquerade called Jonkonnu has been happening for the reason that seventeenth century. A nineteenth century artist described the celebrationIt paints 4 enslaved men playing musical instruments, including a container covered in animal skin in addition to an instrument made out of an animal's jawbone.

In 1861 Narrative of her life in slaveryAbolitionist Harriet Jacobs described the same masquerade in North Carolina.

“Every child gets up early on Christmas morning to see the Johnkannaus,” she wrote. “Without them, Christmas would lose its greatest charm.”

On Christmas Day, she continued, nearly 100 enslaved men marched through the plantation in colourful costumes with cow tails strapped to their backs and horns on their heads. They went door to door asking for donations of food, drinks and gifts. They sang, danced and played musical instruments they made themselves – sheepskin drums, metal triangles and an instrument made out of the jawbone of a horse, mule or donkey.

It's the most effective time to flee from on a regular basis life

But behind the celebration lay an underlying fear through the holiday for enslaved men, women and youngsters.

In the American South, slave owners often sold or rented their slaves in the primary days of the yr to repay their debts. During the week between Christmas and New Year's, many enslaved men, women, and youngsters anxious about the potential of being separated from their family members.

At the identical time, slave owners and their overseers were often distracted—if not drunk—through the holidays. It was a chief opportunity to plan an escape.

John Andrew Jackson was owned by a Quaker planter family in South Carolina. After being separated from his wife and child, he planned to flee through the Christmas holidays of 1846. He managed to flee to Charleston. From there he went north and eventually reached New Brunswick in Canada. Unfortunately, he was never in a position to reunite along with his enslaved relatives.

Even Harriet Tubman took advantage of the holiday break. Five years after her successful escape from the Maryland plantation where she was enslaved, She returned on Christmas Day 1854 to avoid wasting her three brothers from a lifetime of bondage.

It is the time of riot

Across America, the vacations also provided opportunity to plan riots.

In 1811, enslaved and free people of color planned a series of uprisings in Cuba that became referred to as Point Rebellion. The plans and preparations took place between Christmas and the day of the kingsa Catholic holiday on January sixth commemorating the Three Wise Men who visited the child Jesus. Inspired by the Haitian Revolution, free people of color and enslaved people joined together to finish slavery on the island.

The Cuban government finally crushed the rebellion in April.

In Jamaica, enslaved people followed suit. Samuel Sharpe, a enslaved Baptist lay deaconcalled a general strike on Christmas Day 1831 to demand wages and higher working conditions for the enslaved population.

Two nights later, a bunch of enslaved people set fire to a garbage house on a property in Montego Bay. The fire spread and what was presupposed to be a strike changed into a violent riot. The Christmas Riot – or Baptist War because it was called – was the biggest slave revolt in Jamaica's history. For almost two months, hundreds of slaves fought against British forces until they were finally subdued. Sharpe was hanged in Montego Bay on May 23, 1832.

After news of the Christmas Rising and its violent suppression reached Britain, anti-slavery activists increased their calls for slavery to be banned. The following yr, Parliament passed it Slavery Abolition Actwhich banned slavery within the British Empire.

Yes, the week between Christmas and New Year offered the chance to have a good time festivals or plan uprisings.

But more importantly, it was a rare opportunity for enslaved men, women and youngsters to reclaim their humanity.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply