Modern medicine has allowed residents of rich industrialized nations to forget that children once routinely died in frightening numbers. Teaches Nineteenth century English literatureI recurrently come across disheartening depictions of the lack of a baby, and I’m reminded that not knowing the emotional cost of widespread child mortality is a luxury.

In the primary half of the Nineteenth century, between 40% and 50% of youngsters within the USA weren’t older than 5 years. The general child mortality rate, nonetheless, was higher barely lower within the UKBy the early twentieth century, the speed of youngsters living within the poorest slums was near 50%.

The threat of disease was great. Tuberculosis killed an estimated number 1 in 7 people within the US and Europe, and it was that commonest explanation for death within the USA in the primary many years of the Nineteenth century. Smallpox killed 80% of infected children. The high mortality rate of diphtheria and the apparent randomness of its outbreak caused Panic within the press when the disease appeared within the United Kingdom within the late 1850s.

Several technologies are actually stopping the epidemic spread of those and other once-common childhood diseases, including polio, tetanus, whooping cough, measles, scarlet fever and cholera.

Closed sewers Protect drinking water from fecal contamination. Pasteurization kills tuberculosis, diphtheria, typhoid and other pathogenic organisms in milk. Federal regulations Suppliers are prevented from doing so adulterated foods with chalk, lead, alum, plaster of paris, and even arsenic, once used to enhance the colour, texture, or density of inferior products. Vaccines created herd immunity to slow the spread of disease, and antibiotics provide cures for a lot of bacterial diseases.

Because of those health, regulatory and medical advances, the U.S. infant mortality rate is lower than 1% and Great Britain for the reason that Thirties.

Victorian novels chronicle the terrible grief of losing children. They describe the cruelty of diseases which can be largely unknown today and at the identical time warn against being lulled into believing that the death of youngsters can never again be inevitable.

Routine death meant unrelenting grief

Novels tapped into community fears as they mourned fictional children.

Little Nell, the angelic figure at the middle of Charles Dickens' hugely popular “”The old curiosity shop“, disappears from an unnamed illness in the final parts of this sequel novel. When the ship carrying the printed pages with the final part of the story arrived in New York, there were apparently people there shouted from the docksasked if she had survived. The public investments Her death and her grief over it reflect a shared experience of helplessness: no amount of affection can save a baby's life.

Eleven-year-old Anne Shirley from “Green gables“Fame became a hero since it pulled three-year-old Minnie May through a dramatic drama Fight against diphtheria. This was known to readers as a terrible disease through which a membrane blocks the throat so badly that a baby gasps for air.

Children were acquainted with the risks of illness. While typhus in “Jane Eyre13-year-old Helen Burns, who killed almost half the women at her charity school, is battling tuberculosis. Ten-year-old Jane is horrified on the possible lack of the one one who ever truly cared about her.

Mark A. Anderson Collection of Post-Mortem Photographs/William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan

An entire chapter deals openly and emotionally with all this dying. Unable to bear the separation from the quarantined Helen, Jane visits her one night, crammed with “the fear of seeing a corpse.” In the cold of a Victorian bedroom, she slips under Helen's blankets and tries to stifle her own sobs as Helen is overcome by coughs. A teacher spots her the following morning: “My face on Helen Burns' shoulder, my arms around her neck. I was sleeping and Helen was – dead.”

The disturbing image of a sleeping child nestled against one other child's corpse could seem unrealistic. But it is rather much like the mid-Nineteenth century souvenir photos Photographs of deceased children surrounded by their living siblings. Such scenes remind us that the specter of death was at the guts of Victorian childhood.

Fiction was no worse than fact

Victorian periodicals and private writings remind us that the indisputable fact that death is common doesn’t make it any less tragic.

Darwin was tormented by the lack of “the Enjoyment of the household“, when his ten-year-old daughter Annie fell ailing with tuberculosis in 1851.

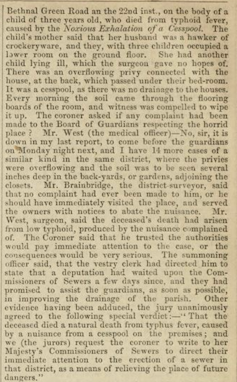

The weekly magazine Household Words reported the death of a three-year-old in 1853 from typhus in a London slum contaminated by an open cesspool. But higher housing was no guarantee against waterborne infections. President Abraham Lincoln was “shocked” and “unnerved” and his wife was “heartbroken” as she watched their son Willie, 11, die of typhus within the White House.

Household Words, January 1853, p. 10, CC BY-SA

In 1856 Archibald Tait, then headmaster of Rugby and later Archbishop of Canterbury, lost five of his seven children to scarlet fever in only over a month. At the time, in response to medical historians, this was the case most steadily pediatric infectious disease within the USA and Europe, fatal 10,000 children per 12 months in England and Wales alone.

Scarlet fever is now generally curable with a 10-day course of antibiotics. However, Researchers warn that recent outbreaks show that we cannot chill out our guard against infection.

Forget at your individual risk

Victorian fiction still lies on children's deathbeds. Modern readers unaccustomed to serious evocations of communal grief may scoff at such sentimental scenes since it is less complicated to laugh at perceived exaggerations than to confront them openly Ghost of a dying child.

“She was dead. Dear, gentle, patient, noble Nell was dead.” Dickens wrote in 1841at a time when a quarter of all children He knew he could die before maturity. For a reader whose own child could easily swap places with Little Nell and turn out to be “forever mute and motionless,” the sentence is an outburst of parental grief.

These Victorian stories evoke a deep, culturally shared grief. To dismiss them as old-fashioned is to assume that they’ve turn out to be obsolete due to the passage of time. But the collective pain of high child mortality was erased not by time but by effort. Rigorous sanitation reform, food and water safety standards, and widespread use of disease control tools resembling vaccines, quarantine, sanitation, and antibiotics are the selection.

And the successes that result from these decisions can dissolve as people begin to make different health decisions.

Although tipping points vary by disease, epidemiologists agree that even small declines in vaccination rates can impact herd immunity. Infectious disease experts And Public health officials are already warning about it dangerous increase in diseases whose horrors made wealthy societies forget the advances of the twentieth century.

People who wish to abolish a century of harsh health measures like a vaccinationinvite these horrors to return.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply