A physicist, a chemist and a mathematician walk right into a bar. It appears like the beginning of a nasty joke, but in my case it was the beginning of an idea that might change the best way scientists think concerning the history of the moon.

The three of us were all involved in the moon, but from different perspectives: As a geophysicistI thought of his insides; Thorsten Kleine studied his chemistry; And Alessandro Morbidelli desired to know what the formation of the moon could tell us how the planets were put together 4.5 billion years ago.

When we got here together to debate how old the moon really was, having these diverse perspectives proved crucial.

How was the moon formed?

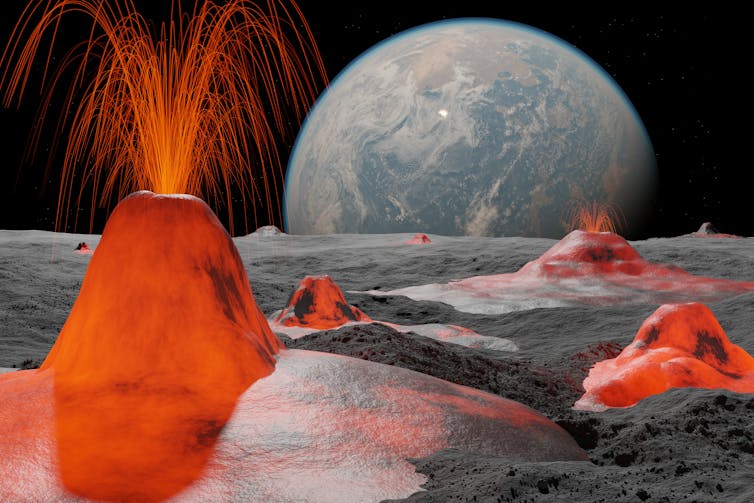

At a Conference in Hawaii At the top of the Nineteen Eighties, a bunch of scientists solved the issue of the formation of the moon. Their research suggested that a Mars-sized object crashed into early EarthMolten material is thrown into space. This glowing material coalesced into the body now called the moon.

This story explained many things. For one thing, the moon has little or no Material that evaporates easilylike water, because life began to melt. It only has one tiny iron coresince it was largely formed from the outer a part of the earth, which accommodates little or no iron. And it has a buoyant, white coloured crust Minerals that floated to the surface because the molten moon solidified.

The vibrant, newly formed moon was initially very near Earth approximately the space that television satellites orbit. The early Moon would have triggered gigantic tides on the early Earth, which itself was mostly melted and spinning rapidly.

These tides extracted energy from Earth's rotation and transferred a few of it to the Moon's orbit, slowly pushing the Moon away from Earth and slowing Earth's rotation in the method. This movement continues to at the present time – the moon continues to be moving away from the Earth 2 inches per 12 months.

MPS/Alexey Chizhik

As the moon moved away, it passed certain points where its orbit was momentarily perturbed. These orbital perturbations were a very important a part of its history and a central a part of our hypothesis.

When was the moon created?

When the moon actually formed and moved away from Earth is a difficult query.

Thanks to the Apollo astronauts, scientists have one Collection of moon rockswhose age they’ll measure. The oldest rocks are all about 4.35 billion years oldi.e. about 200 million years after that Birth of the solar system.

Many geochemists, like my colleague Thorsten Kleine, suspected (not without reason) that the age of those rocks corresponds to the age of the moon.

But people like Alessandro Morbidelli, who study planet formation, didn't particularly like that answer. In their models, planets swept up many of the matter floating across the early solar system long before 200 million years had passed. An enormous, moon-forming impact at a later date than the rock samples suggested seemed fairly unlikely.

What did we advise?

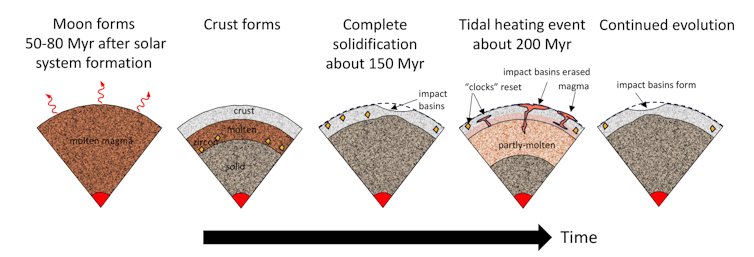

This is where Kleine, Morbidelli and I got here into play. We followed up on a suggestion from a 2016 study that found the moon could occasionally experience extreme warming events during its slow journey outward from Earth.

This warming occurs in the identical way because the warming on Jupiter hyperactive volcanic moon Io. The shape of the smaller body is compressed and stretched by the tides of the larger body. And just as a rubber ball heats up if you squeeze it enough, the rocks on Io and the Moon also heat up.

All rocks contain small internal clocks – radioactive elements that decay and permit researchers to decay Tell me how old the stone is. But here's the important thing point: If the moon warmed enough, its clocks would lose their memory and only start keeping time once the moon cooled again.

In this image, the gathering of roughly 4.35 billion-year-old rocks doesn't tell us when the moon was formed, only when it underwent this tidal warming. This signifies that the moon's formation will need to have occurred earlier.

An early date of formation satisfies physicists studying planet formation, while also explaining that the later dating determined from the rocks is resulting from it Tidal warming.

Francis Nimmo

What's next?

As is usually the case in science, two groups got here up with the same idea at the identical time. During the research, our group focused on a tidal warming event that occurred when the Moon was quite removed from Earth Steve Desh at Arizona State University points to an event that took place when the moon was closer. It will take time to work out which of those two hypotheses is correct – and maybe neither is correct.

To test these hypotheses, more samples from the Moon are needed. Fortunately, China's Chang'e Mission 6 I just returned samples from the dark side of the moon in June 2024. If these samples also show many rocks, throughout 4.35 billion years old, that will be consistent with our story. When the ages are much older, we’ve to think up a brand new story.

Very often geochemists and geophysicists find yourself in earth and planetary sciences different and contradictory hypotheses. This is partly because these fields use several types of measurements, but in addition because they speak very different scientific languages. Overcoming this language barrier is difficult.

Our study is an example of how – sometimes – bridging this linguistic and scientific divide can profit researchers on either side.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply