Local news

As Massachusetts residents leave the state resulting from high transportation and living costs, there may be great pressure to construct more multifamily housing in transit-accessible areas of the Greater Boston area.

And while supporters claim the MBTA Communities Act will just do that, there may be a growing tide of opposition in several cities and towns that now face a deadline to expand their zoning.

Medway and Winthrop are among the latest flashpoints within the fight over the MBTA law that requires 177 communities that serve or are near the T line to construct more multifamily housing. The law, signed by former Gov. Charlie Baker in 2021, has faced opposition from some who say the zoning ordinance is simply too broad or represents an overreach of state authority.

“I think this is a one-size-fits-all approach that doesn't allow the state to recognize the uniqueness of each individual community,” said state Rep. Jeffrey Turco, who represents Winthrop and has been a vocal critic of the law.

What does the MBTA Communities Act do?

The MBTA Communities Act sets “unit capacity goals” for every community's zoning — in other words, what number of units might be in-built a given zone if the land were completely undeveloped. By Dec. 31, Winthrop must submit compliance plans to create a theoretical 882-unit zone, while Medway must create a 750-unit zone.

But as Turco points out, these numbers are based on the quantity of housing available in each community and don’t necessarily bear in mind current density or resources.

“I think it becomes an unfunded mandate for local governments and local schools,” Turco said in a phone interview, also comparing the differences between cities like Winthrop and bigger, wealthier communities west of Boston.

“Working-class neighborhoods will suffer the impact of density regulations, but upscale neighborhoods will not,” he said.

In the meantime, Advocates and policy makers say the law is one other tool to assist Massachusetts address its worsening housing crisis. Dozens of communities have already introduced a zoning system is designed to comply with MBTA law, based on the state's Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities. In several other cities, voters have rejected development plans and sent local politicians back to the drafting board.

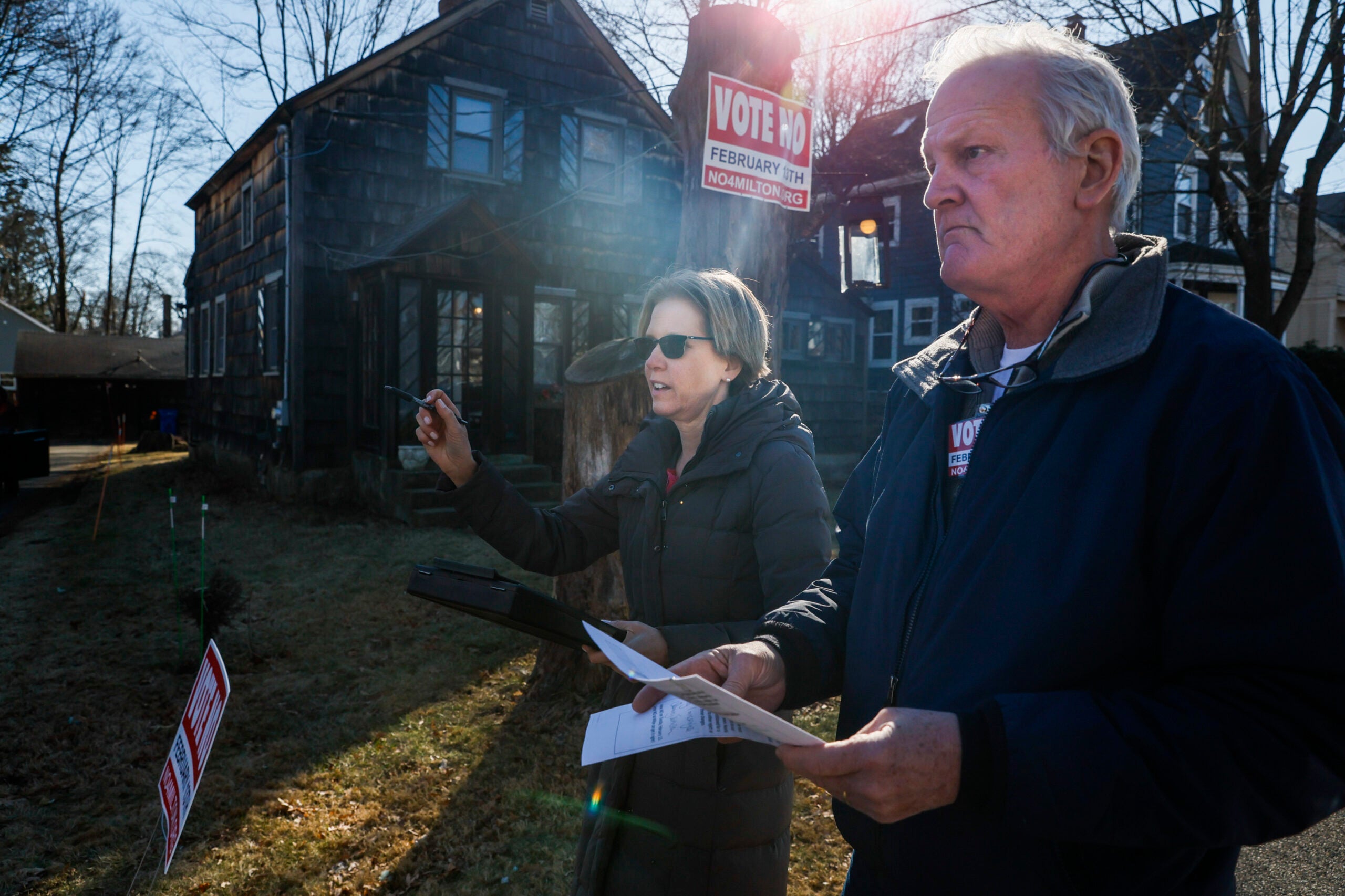

Milton, a “rapid transit community” with a 2023 deadline, led the best way in noncompliance by adopting a zoning plan last yr, only to reverse the changes months later. The city now faces the lack of some state funding, and Attorney General Andrea Campbell has filed suit against Milton for noncompliance. The Supreme Court will hear the case in October.

Another legal battle is underway in Rockport, where a gaggle of residents has filed a lawsuit in federal court difficult town's efforts to comply with the law.

“A hammer over the heads of the working-class communities”

In Winthrop, resistance is raging, the residents have requested The City Council has held demonstrations, organized a citizen forum, and even taken legal motion to stop the zoning changes under the MBTA law.

Already in January, 10 concerned residents founded the group “Winthrop says no to 3A”, a reference to the relevant section of the state constructing code. In response to a series of questions via email, residents said they were concerned that increasing population density could further strain town’s funds and infrastructure, and potentially clog the peninsula’s few exits.

The state has made several changes to the MBTA Communities Act guidelines for the reason that draft requirements were released in 2021, and affected Winthrop residents argue that evolving guidelines pose a challenge to effective, long-term planning. On the opposite hand, state Housing Secretary Edward Augustus told the Winthrop City Council in a February meeting letter that the changes “significantly reduced” the burden on town while giving Winthrop more flexibility in defining its multifamily housing district.

However, Turco said that the announced flexibility only applies if the communities are already committed to higher density and more housing.

“It doesn't give a community flexibility to say, 'The local conditions don't require us to increase density, don't require additional housing units,'” he said. “So there's no flexibility there. It's basically a hammer hitting working-class communities over the head.”

In Medway, the town council sent a letter to Governor Maura Healey and other state officials who expressed the community’s formal opposition to the bill last month, reported. Medway has delayed a vote on the zoning changes until the town hall meeting in November to collect as much information as possible from the state and other cities and towns that oppose the bill, select committee member Dennis Crowley said in a phone interview.

He said the community's concerns were mixed, with some fearing a hypothetical wave of recent residents that might overwhelm the town's schools, require more emergency services and possibly even cause Medway to exceed its water and sewerage capability.

Others worry that the brand new zoning could disrupt their neighborhood.

“It's a 'not in my backyard' thing,” Crowley said. “And it's justified because if it were in my area, I would be addressing the same issues myself.”

What happens if cities and municipalities don’t comply with the regulations?

Milton serves as a cautionary tale of what could occur if MBTA communities fail to satisfy their deadlines. Campbell gave a Advice Clarify that communities that fail to comply may face civil motion, lack of some government funds, and possibly liability under federal and state fair housing laws.

“A coalition of Democrats and Republicans passed the MBTA Communities Law, and it is my job to enforce it,” Campbell said in a press release. “Compliance with the law is mandatory, and this law is an essential tool to address our housing crisis, which unfortunately is causing more and more residents to leave Massachusetts.”

She stressed that the law gives cities and municipalities “considerable discretion” in relation to introducing zones suitable for his or her community.

“It is nonsense to claim that this law hurts the working class when in reality it helps our public employees, teachers, nurses and paramedics stay and live in the community of their choice,” Campbell said.

While Turco said he doesn’t want Winthrop or some other municipality to lose state incentives, he stressed that “the damaging effects of a developer gold rush in Winthrop will far outweigh the loss of state incentives.”

He suggested the East-West Railroad project might be a greater use of state resources. It would improve rail service to Western Massachusetts and, supporters say, provide viable housing solutions outside of the Boston metropolitan area.

Like Turco, “Winthrop Says No to 3A” also argued that the associated fee of implementing the MBTA law across town’s 1.6 square miles “is simply more than we can bear as a community.”

The group also said that as a substitute of penalties, the state should offer incentives to cities and towns that may address the MBTA Communities Act's zoning changes and provides communities the chance to opt out without risk of litigation or lack of funding.

“If Milton loses in October, we will appeal until we win,” Winthrop residents said. “The law is unconstitutional and we will not be intimidated by the state. It is disheartening to be treated this way by the very people we elected and trust to represent us.”

image credit : www.boston.com

Leave a Reply