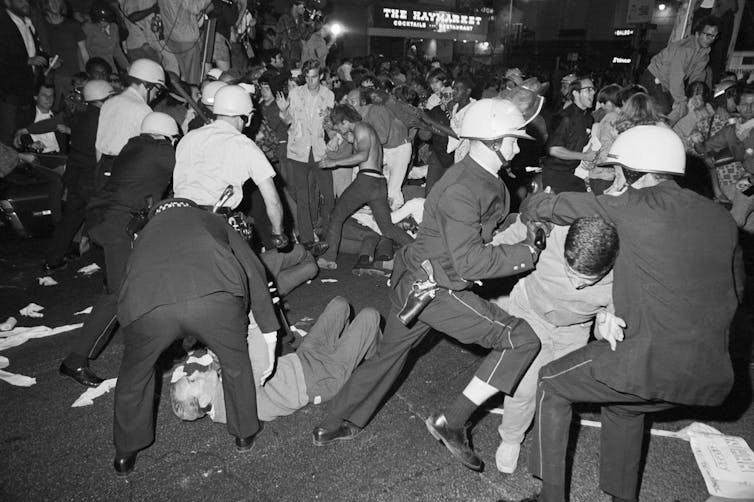

On the third day of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, Chicago police beat protesters in a scuffle on Michigan Avenue. iconic images of this close combat have since been in almost every Documentary about America within the Nineteen Sixties or in regards to the war in Vietnam.

But these should not the one images from those dark days. In fact, Chicagoans have recently been rewatching a few of the very best movies of the era, as interest in stories in regards to the history of the Democratic National Convention during that violent and tumultuous 12 months is big, sparked by the choice to carry the convention this 12 months in the identical city where the riots had previously occurred.

In late spring 2024, 4 short 1969 Documentaries of the Chicago Film Group were shown in Chicago Cultural Center. Film Group was a successful promoting producer for clients similar to Kentucky Fried Chicken. In the summer of 1966, they expanded their repertoire to incorporate political movies when Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference got here to town to take part in an ultimately futile Fighting discrimination when on the lookout for housing.

Bettman/Getty Images

The theater was filled with journalists, octogenarian activists and a handful of 50-year-olds. like meeveryone is happy to see these gripping documentaries, which contain not only famous shots of Michigan Avenue, but in addition images which were much less circulated since 1968.

This included Mayor Richard Daley, who declared after King’s assassination that the police should “Shoot to kill arsonists” and “Shoot to maim or cripple any looter“ – suggestions that, as he later claimed, he had never made.

“Devastating indictment” against Daley

At the tip of July 2024, the Music Box Theatre showed one other short film from the Film Groupfollowed by Haskell Wexler’s “Medium Cool“, a drama about an almost completely amoral television news cameraman.

The film tells its story in two alternative ways. One scripted and at times relatively stiff storyline follows a budding relationship between the cameraman and a young woman from Appalachia. The other, connected story is unscripted and more explicitly political. It includes documentary footage of the road violence of 1968 and interviews with black activists, and raises questions on media ethics and the policies of Daley's police force.

Ultimately, the film is a scathing indictment of each Daley's “law and order” tactics – language Daley used that was paying homage to Richard Nixon – and tv itself. It celebrates the film's depth while exposing the superficial superficiality of what snobs once called “idiot box” television.

The house was full. To my right sat a movie student who was there on the insistence of his professor. The place was indeed filled with young film buffs, enraptured by an introduction by Julian Antos of the Chicago Film Societywho celebrated the undeniable fact that the town finally has its own recent 35mm print of this most Chicago-esque film. Dibbell added one other detail that thrilled film geeks: He explained that the film's roller derby scene reintroduced a fun song that was long missing from the streaming and DVD versions of “Medium Cool” as a consequence of rights issues.

To my left sat three older men who had worked with Wexler within the Nineteen Seventies. One had seen Medium Cool several times, however it had been some time since. He later accurately noted that an excellent editor could have cut 20 minutes to tighten up the film's skewed pace.

When I saw it again for the umpteenth time, I used to be particularly struck by the gaps within the political context, that are in contrast to the Film Group productions. “Medium Cool” offers a sharp criticism of violence and media exploitation this violence, and reference is made to Chicago's Red Squad – a police surveillance unit directed against communists and others are considered “radical” – that will have escaped many viewers then and now.

However, Wexler assumed that viewers in 1969 already knew most of the small print of the 1968 presidential campaign. What does this mean for viewers today who should not taken with the story greater than half a century later?

Chicago Film Society, From

“I won’t take it anymore”

As I left the theater, I finished to talk over with an brisk young woman who was preparing for a march in support of reproductive and queer rights. and against the Democratic Convention and the genocide within the Gaza Strip.

She felt that Kamala Harris was not that different from Joe Biden and that neither politician was greater than barely higher than Donald Trump. As for the film, she didn't care in any respect in regards to the hero, but she said the sound design was exceptional – fair criticism and appropriate praise.

It appeared like Medium Cool didn't teach her all that much about 1968, and yet her stance on systemic injustice resonated with me as a historian. Few activists got here to the 1968 Democratic National Convention to support presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey or to attack Nixon. These men simply weren't the main target. They were there to protest the entire rattling crisis of American politics.

The 12 months is 2024, not 1968, but movies about this era in American politics capture a sense that’s resurfacing nearly 60 years later. It is probably going that the streets of Chicago will soon be filled again with individuals who, as protagonist Howard Beale said in his famous tirade within the film Network, “I'm mad as hell and I won't take this anymore.”

This story has been updated with the proper name of Chicago Film Society staff author Julian Antos.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply