After World War II, trials of Nazi officials accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity were held in Nuremberg. The Nuremberg trials were milestones in the event of international law. But considered one of them was also applied in peacetime: the “Medical study”, which has shaped bioethics ever since.

Twenty Nazi doctors and three administrative employees were placed on trial for deadly and painful experiments on humansincluding freezing prisoners in ice water and simulated high-altitude experiments. Other Nazi experiments included infecting prisoners with malaria, typhus and poisons, in addition to administering mustard gas and sterilization. These criminal experiments were mostly carried out in concentration camps and infrequently led to the death of the test subjects.

Lead prosecutor Telford Taylor, an American lawyer and general within the US Army, argued that such deadly experiments were more accurate classified as murder and torture than anything related to the practice of medication. A review of the evidence, including Doctor as expert And Testimonies from survivors of the campled the judges to achieve an agreement. The verdicts were announced on August 20, 1947.

As a part of their ruling, the American judges formulated what was referred to as The Nuremberg Codethat set out the important thing requirements for ethical treatment and medical research. The Code is well known as, amongst other things, the primary major articulation of the doctrine of informed consent. Yet its guidelines will not be sufficient to guard people today from latest, potentially “species-endangering” research.

10 Key Values

The code consists of 10 principles that the judges' decision should be followed for reasons of each medical ethics and international human rights.

The first and most famous sentence stands out: “The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely necessary.”

In addition to free and informed consent, the Code also requires that subjects have the best to withdraw from an experiment at any time. The other provisions are designed to guard the health of subjects. This includes that research must only be carried out by a certified researcher, should be based on sound scientific evidence, should be based on preliminary studies on animals, and must ensure adequate health and safety protection for subjects.

The prosecutors, doctors and judges of the trial formulated the code in collaboration. Set the agenda early for a brand new field: bioethics. The guidelines also describe a relationship between scientist and subject that requires researchers to not only act in the perfect interests of the topics, but in addition to respect the human rights of the topics and protect their well-being. These rules essentially replace the paternalistic model of the Hippocratic Oath with a human rights approach.

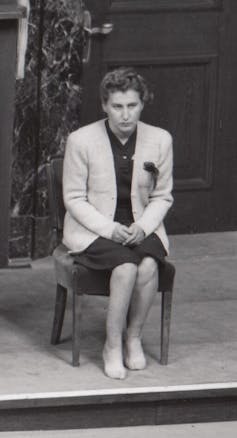

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum via Wikimedia Commons

Under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the commanding general in Europe, adopted the principles of the Code in 1953 – an indication of his influence. His fundamental principle of consent can also be summarized within the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rightswhich states: “No one shall be subjected to medical or scientific experimentation without his or her free consent.”

Nevertheless, some doctors tried to distance themselves from the Nuremberg Code since it was more legal than medical in nature and since they didn’t wish to be associated in any way with the Nazi doctors on trial in Nuremberg.

The World Medical Association, a medical association founded after the Nuremberg Trials, formulated its own ethical guidelinescalled “Declaration of Helsinki.” Like Hippocrates, Helsinki allowed exceptions to the informed consent requirement, for instance when the physician-researcher believed that silence was within the patient’s best medical interest.

The Nuremberg Code was written by judges to be used within the courtroom. Helinski was written by doctors for doctors.

Since Nuremberg, there have been no further international trials with regards to human experimentation, including before the International Criminal Court, so the text of the Nuremberg Code has remained unchanged.

New research, latest procedures?

The Code was a serious focus of my work on health law and bioethicsand I spoke at conferences in Nuremberg on the occasion of its fiftieth and seventy fifth anniversaries, sponsored by the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. At each events, the Nuremberg Code was recognized as a declaration of human rights.

Office of the Military Government for Germany (USA) via Wikimedia Commons

I remain a robust supporter of the Nuremberg Code and imagine that compliance with its principles is each an ethical and legal obligation for physician researchers. However, the general public cannot expect the Nuremberg Code to guard them from all sorts of scientific research or weapons development.

Soon after the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki – two years before the Nuremberg trials began – it became clear that our species was able to destroying itself.

Nuclear weapons are only one example. Recently, the international debate has focused on latest potential pandemics, but in addition on “gain-of-function” research, which sometimes involves making existing bacteria or viruses more deadly to make them more dangerous. The goal shouldn’t be to harm people, but somewhat to attempt to develop a protective countermeasure. The danger, after all, is that an especially dangerous agent could “escape” the lab before such a countermeasure could be developed.

I agree with critics who argue that at the very least some gain-of-function research is so dangerous to our species that it must be banned altogether. Innovations in artificial intelligence and Climate Engineering could also pose a deadly danger to all humans, not just a few. Our next query is who gets to come to a decision whether species-endangering research must be carried out and on what basis?

I imagine that research that endangers species must be subject to multinational, democratic debate and approval. Such a mechanism can be one method to make the survival of our own endangered species more likely – and make sure that we will have a good time the one hundredth anniversary of the Nuremberg Code.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply