Nineteen-year-old US Army Pvt. David Lewis set out along with his unit from Fort Dix on a 50-mile hike on February 5, 1976. On that bitterly cold day, he collapsed and died. Autopsy samples unexpectedly returned a positive result for a H1N1 swine flu virus.

Viral disease surveillance at Fort Dix identified an extra 13 cases amongst recruits hospitalized for respiratory illnesses. Additional serum antibody testing revealed that over 200 recruits were infected but not hospitalized with the virus. latest swine strain H1N1.

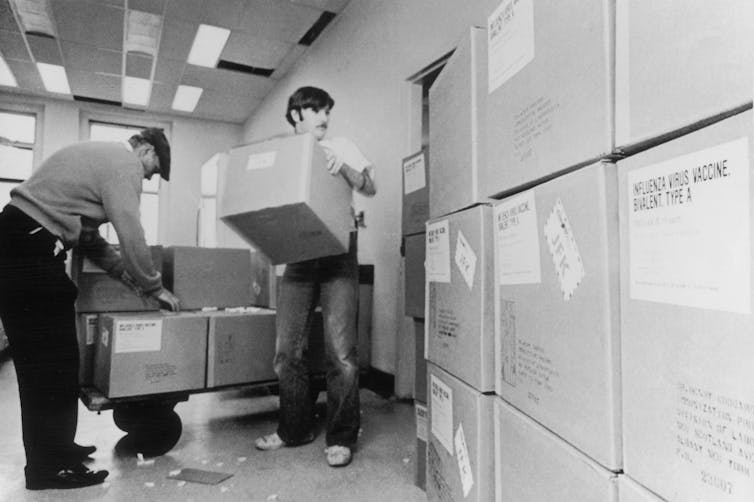

PhotoQuest/Getty Images

Alarm bells immediately rang within the epidemiological community: Could Pvt. Lewis' death from H1N1 swine flu be a harbinger of one other global pandemic, just like the terrible H1N1 swine flu pandemic of 1918, by which a an estimated 50 million people worldwide?

The US government reacted quickly. On March 24, 1976, President Gerald Ford announced a plan to “vaccinate every man, woman and child in the United States.” On October 1, 1976 Mass vaccination campaign began.

Meanwhile, the initial small outbreak at Fort Dix had quickly subsided, and there had been no latest cases on the bottom since February. Army Col. Frank Top, who led the investigation into the virus at Fort Dix, later told me, “We had shown pretty conclusively that (the virus) had not crossed over anywhere else but Fort Dix… it disappeared.”

Nevertheless, biomedical scientists world wide are concerned about this outbreak and the huge crash vaccination program within the United States. began research and development programs for H1N1 swine flu vaccines in their very own countries. At the start of the 1976/77 winter season, the world was waiting for – and preparing for – an H1N1 swine flu pandemic that never got here.

AP Photo/Jim McKnight

But that wasn't the tip of the story. an experienced infectious disease epidemiologistI claim that it unintended consequences of this seemingly prudent but ultimately unnecessary preparations.

What was strange concerning the Russian H1N1 flu pandemic?

In an epidemiological twist, a brand new pandemic influenza virus emerged, nevertheless it was not the expected H1N1 swine virus.

In November 1977, Russian health officials reported that a human, not a swine, strain of H1N1 flu had been discovered in Moscow. By the tip of the month, the disease had been reported throughout the USSR and soon all around the world.

Compared to other varieties of flu this pandemic was strangeFirst, the fatality rate was low, about one-third that of most flu viruses. Second, it repeatedly infected only people under the age of 26. Finally, unlike other newly emerged pandemic flu viruses prior to now, the virus didn’t displace the already dominant H3N2 subtype that caused the seasonal flu this yr. Instead, the 2 flu viruses – the brand new H1N1 and the long-standing H3N2 – circulated alongside one another.

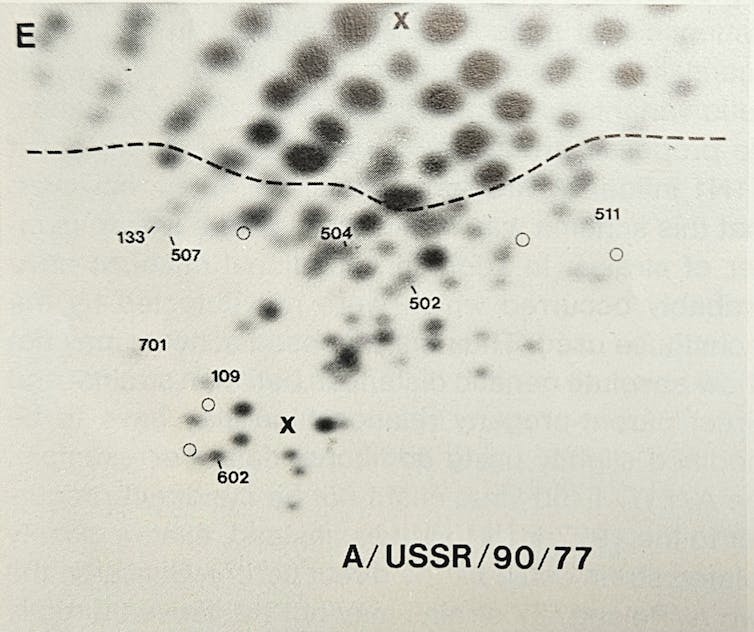

Here the story takes one other turn. Microbiologist Peter Palese applied, which at the moment was a latest technique called RNA oligonucleotide mapping to check the genetic makeup of the brand new Russian flu virus, H1N1. He and his colleagues grew the virus within the lab after which used RNA-cutting enzymes to cut the viral genome into a whole lot of pieces. By distributing the chopped RNA in two dimensions based on size and electrical charge, the RNA fragments created a singular, fingerprint-like patch map.

Peter Palese

To Palese's great surprise, it turned out that this “new” virus was essentially similar to older human influenza H1N1 strains which became extinct within the early Nineteen Fifties.

So the 1977 Russian flu virus was actually a strain that had disappeared from the planet 1 / 4 century earlier after which someway got here back into circulation. This explained why it only affected younger people—older people had already been infected and turn out to be immune when the virus was circulating in its earlier form a long time ago.

But how could the older variety turn out to be extinct again?

Gilbert UZAN/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Refining the timeline of a resurrected virus

Despite its name, the Russian flu probably didn’t begin in Russia. The first published reports of the virus got here from Russia, but later reports from China provided evidence that it had first been detected months earlier, in May and June 1977. within the Chinese port city of Tientsin.

In 2010, scientists used detailed genetic studies on several samples of the 1977 virus to determine the date of their earliest common ancestorThese “molecular clock” data suggest that the virus first infected humans a full yr earlier, in April or May 1976.

So the most effective evidence is that the Russian flu of 1977 actually occurred – or slightly “reoccurred” – in or near Tientsin, China, within the spring of 1976.

A frozen laboratory virus

Was it only a coincidence that inside a couple of months of Private Lewis' death from swine flu H1N1, a previously extinct strain of influenza H1N1 suddenly reappeared within the population?

For years, influenza virologists world wide used freezers to store flu viruses, including people who had turn out to be extinct within the wild. Fear of a brand new H1N1 swine flu pandemic within the United States in 1976 had sparked a world Increase in research into H1N1 viruses and vaccinesThe accidental release of certainly one of these stockpiled viruses would have been entirely possible in any country conducting H1N1 research, including China, Russia, the United States, the United Kingdom, and doubtless other countries.

Years after the disease re-emerged, microbiologist Palese recalled personal conversations he had had with Chi-Ming Chu, the leading Chinese flu expert. Palese wrote in 2004 that “the introduction of the H1N1 virus in 1977 is now considered Result of vaccine trials in the Far East “Several thousand military recruits will be infected with the live H1N1 virus.”

Although it is just not known exactly how such an accidental release could have occurred during a vaccine trial, there are two possibilities. First, scientists could have used the resurrected H1N1 virus as a starting material for the event of a live, subdued H1N1 vaccine. If the virus had not been sufficiently weakened within the vaccine, it might have been transmissible from individual to individual. Another possibility is that researchers used the live, resurrected virus to check the immunity provided by conventional H1N1 vaccines and it unintentionally escaped from the research setting.

Whatever the precise mechanism of release, the mix of the precise location and timing of the pandemic's origin and the status of Chu and Palese as highly credible sources strongly suggests that the Russian flu virus originated from an accidental release in China.

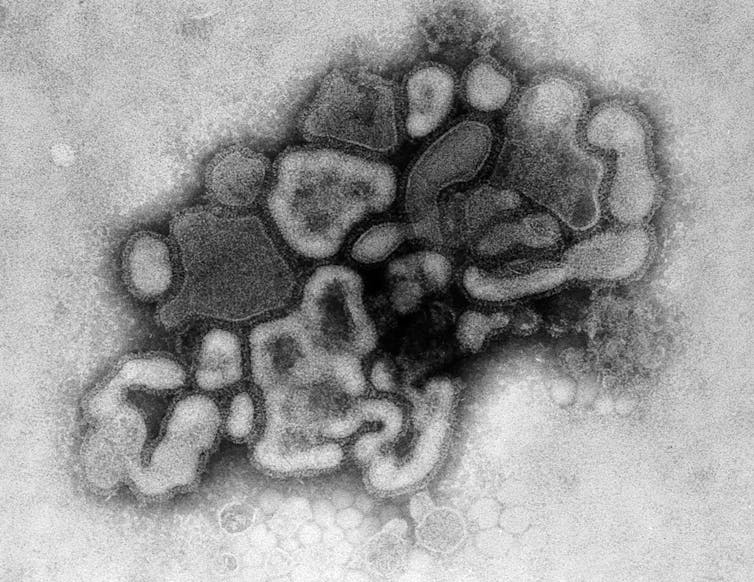

CDC/Dr. E. Palmer, RE Bates, 1976 via Getty Images

A sobering history lesson

The resurgence of an extinct but dangerous human-adapted H1N1 virus occurred because the world scrambled to stop what was regarded as an imminent outbreak of a swine flu pandemic. People were so anxious about the opportunity of a brand new pandemic that they inadvertently triggered one. It was a pandemic that could be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

I’m not attempting to assign blame here. Rather, my most important argument is that within the epidemiological fog of 1976, when fear of an impending pandemic was growing worldwide, a research unit in any country could have unintentionally released the resurrected virus that may later be called the Russian flu. In the worldwide rush to stop a possible latest pandemic of H1N1 swine flu from Fort Dix through research and vaccination, accidents could have happened anywhere.

Of course, biosecurity facilities and policies have improved dramatically during the last half century. But at the identical time, there was an equally dramatic Proliferation of high-security laboratories world wide.

AP Photo/Michael Probst

Overreaction. Unintended consequences. Worsening of the situation. Self-fulfilling prophecy. There are a wide range of terms to explain how the most effective intentions can go awry. The world remains to be reeling from COVID-19 and now faces latest threats from the cross-species spread of avian influenza viruses, mpoxviruses and other viruses. It is critical that we respond quickly to those latest threats to stop one other global disease outbreak. Quickly, but not too quickly, as history shows.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply