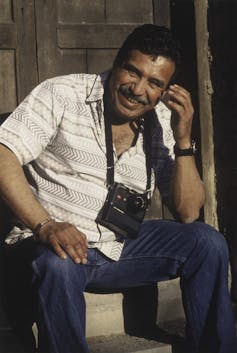

Louis Carlos Bernala Chicano photographer born within the border town of Douglas, Arizona in 1941, developed a sort of high-quality art photography that celebrated his Mexican-American culture, creating an indelible document of life within the Southwest's barrios – poor, predominantly Hispanic neighborhoods – within the Seventies and Eighties.

He died tragically in 1993 on the age of just 52. With his photographs present in only just a few museum collections, his legacy has been largely ignored over the past three a long time. Now his powerful images are reaching a brand new audience through a bilingual book and exhibition of 120 photographs.

As chief curator of the Center for Creative Photography on the University of Arizona, I even have worked with Bernal's photographs for the past decade. In 2014, his family donated his photographs, negatives, contact sheets, working materials and memorabilia, enabling us to Louis Carlos Bernal Archive within the highlight.

The exhibition, which runs from September 14, 2024 to March 15, 2025, features portraits of on a regular basis Mexican Americans from his most famous photo series, “Barrios.” And because of the work of the photography scholar Elisabeth Ferrerwe learned much more about Bernal’s artistic technique, processes and goals.

Capturing “Chicanismo”

As a toddler, Bernal was given a camera and have become fascinated with photography. He enrolled at Arizona State University considering he would turn into a Spanish teacher, but his fascination with photography won out.

Bernal pursued various projects while deepening his exploration of photography. He created collages with iconic images of former President John F. Kennedywho was the primary Catholic president was especially revered within the Mexican-American community. In response to the Watergate hearings and since he was enthusiastic about the effect of the media on public perception, he worked on a series during which he instructed relations to carry a life-size mask of Richard M. Nixon in front of their faces. In keeping with the work of certainly one of his mentors, the visual artist Frederick Sommerhe created abstract images with sculpturally cut paper.

Ultimately, these experiments led to a comprehensive and sustained project of photographing Mexicans and Americans in Mexico and their homeland.

He made his neighbors, relatives, and other Chicanos living within the Southwest his artistic subjects. Together, the pictures convey Bernal's goal of expressing his Mexican-American pride, often called “Chicanism.”

In this fashion he was a part of the Chicano art movementthat sought to deal with the political and cultural concerns of the Mexican-American community. Chicano artists addressed issues equivalent to labor exploitation, immigration, gender roles, and racial discrimination. Their goal was to interrupt stereotypes about Mexican Americans, critique the establishment, and cultivate a shared cultural identity.

“Art by the people and for the people”

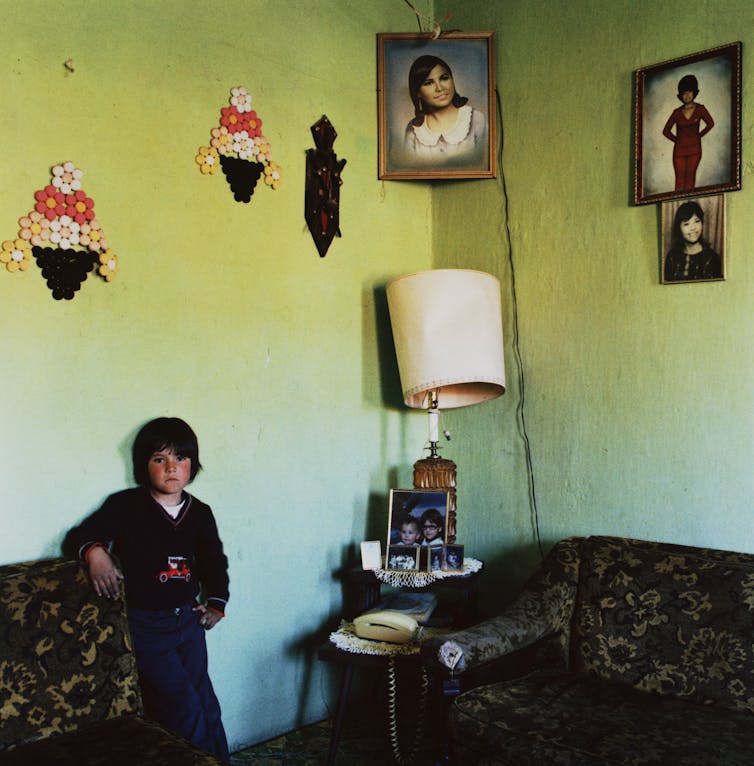

Bernal’s photographs may remind some viewers of snapshots from a family album, and indeed they’ve many things in common with family photos: They show people in Everyday settings; the themes are sometimes centered, pose naturally and appear relaxed; and he preferred color photography, which within the Seventieshad turn into a well-liked option to document birthday parties, holidays, and other family milestones.

Bernal, then again, put a variety of thought into the weather in each photograph. He developed a process to create images exactly as he imagined them.

In the numerous photographs he took in homes and businesses, in addition to at gatherings of relatives and friends, he deliberately highlighted personal possessions: framed family photos, altars, posters, religious icons, textiles, and floral and seasonal decorations. Beyond the people in the pictures, he desired to convey themes of family, spirituality, home, and community.

Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive, © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann Bernal

In a Video interview from 1982Bernal described his process and the way he “went through things in his head in advance before he went out.”

This allowed him to work quickly when he was in someone's home and minimise the disruption of his presence. He also liked to photograph variations of the identical setting – for instance, a room with and without relations, or a scene in each color and black and white. Later, he would review all the choices and select the very best from a bunch of images with subtle differences.

Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive, © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann Bernal

This allowed him to create photographs of his surroundings based on his deep familiarity with Chicano life and culture. These images introduced people outside the barrios to a lifestyle. But additionally they held up a mirror to other Mexicans, as they might easily recognize the scenes.

“The Chicano artist cannot isolate himself from the community,” Bernal said in 1984“but finds himself in the midst of his people, where he creates art by the people and for the people.”

Enhancing on a regular basis life

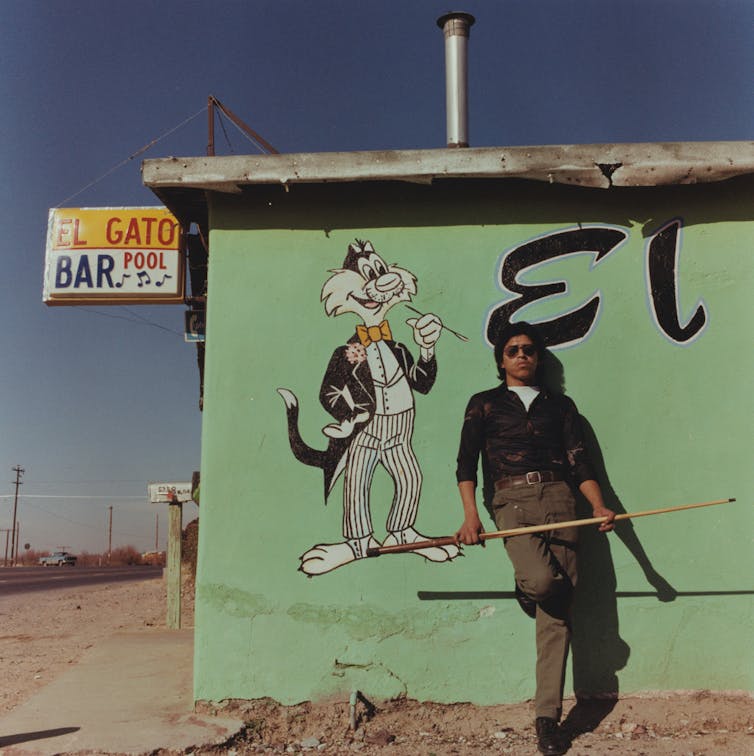

Bernal's approach may be illustrated by some typical portraits.

In “6th Street Barrio, Douglas, Arizona, 1979,” Bernal photographs a bit boy within the front room of his family’s home.

Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Purchase, © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann Bernal

The boy represents one point of a triangular composition. A dark brown upholstered sofa acts as the opposite, while family photographs high on the yellow wall form the apex. Bernal has settled in opposite the corner of the room, where a small side table with the family's belongings stood.

The triangular arrangement of the photograph's principal elements—and the symmetry of the vertical line formed by the corner of the room in the middle—give the image balance, stability, and permanence, reflecting the way in which during which family and residential function anchors for the Chicano community.

In “Leon Speer's Barber Shop, Felix Valdivezo & Daughter Patricia, Lordsburg, New Mexico, 1978,” Bernal places the barber shop wall parallel to his lens. This selection creates an organized, serene, and easy-to-understand environment during which to take a photograph of the barber, the client, and the client's daughter.

Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Gift of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann Bernal

Through this attitude—and with the assistance of a series of mirrors and lights—Bernal captures a small world in its entirety, from the tiled floor reflecting sunlight to the gathering of objects on a shelf beneath the pressed-sheet ceiling. In this fashion, Bernal elevates an abnormal place and abnormal people into something special to behold. Rather than the spontaneous and unaffected qualities one might expect from casually documenting, say, a toddler's first haircut, Bernal has taken a deliberate and formal approach that makes a well-known subject worthy of art.

Bernal's legacy

Bernal was within the means of creating this incredible document of latest Mexican-American culture when his life got here to an abrupt end.

Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive, © 1988 Edward McCain

He had built the photography program at Pima Community College in Tucson, Arizona, and his photography practice was thriving. But in 1989, he was hit by a automotive while bicycling to work. He spent the subsequent 4 years in a coma and died on his birthday in 1993 on the age of 52.

Although he had gained recognition within the United States, his profession was more widely known in Mexico, where he had built a robust community and a thriving skilled network. After his death, his work was not widely distributed within the United States

With the establishment of his archive, the publication of “Louis Carlos Bernal: Monograph” and the opening of a significant exhibition honoring his work, I hope that his Chicano pride and artistic vision will probably be delivered to a brand new generation of viewers, thus enshrining his legacy within the history of American art.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply