In response to The failure of national pollsters In predicting election ends in 1948 and 1952, the New York Times conducted a week-long, multistate field reporting exercise in 1956 to gauge public opinion concerning the presidential election.

The Times' experiment, now often called “Shoe Leather CoverageThis included two dozen journalists assigned to four teams that traveled to a total of 27 battleground states several weeks before the election – a rematch between President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Republican, and his Democratic rival Adlai E. Stevenson.

The reporting teams surveyed scores of Americans from all walks of life to qualitatively gauge voter preferences—without counting on pre-election poll data. One of the participating Times reporters said afterwards that team-based campaign reporting represented “a new departure in journalism.”

In unintended evidence of the challenges of measuring public opinion across a sprawling country, the Times' reporting was not a big improvement over the polls. The Times' reporting notably didn’t foresee the extent of Eisenhower's re-election – a one-sided victory during which he carried 41 states.

In his Final report Before the election, the Times concluded that Eisenhower would win re-election but wouldn’t repeat the successes he had achieved 4 years earlier. As it turned out, Eisenhower exceeded them Dimensions of his victory in 1952when his winning margin was 10.5 percentage points.

The Times' reporting was also unpredictable Eisenhower's state victories in 1956 VirginiaOklahoma and West Virginia, and significantly underestimated the president's support in Connecticut, Illinois, MichiganMinnesota, Pennsylvania and Texas, amongst other states.

The Times' reporting experiment proved to be an imperfect substitute for election polls, as I argued in a recent research paper for The Times American Journalism Historians Association. In the work I defined “Shoe Leather Coverage” as a group of current content through personal interviews, document searches and on-site observations. The idiom assumes that journalists do their fieldwork so vigorously that they wear out their shoes.

“Shoe leather reporting” has been around for a very long time celebrated in American media; a widely published journalism educator described the practice as “mythical” and “one of the few gods to whom an American journalist can officially pray.”

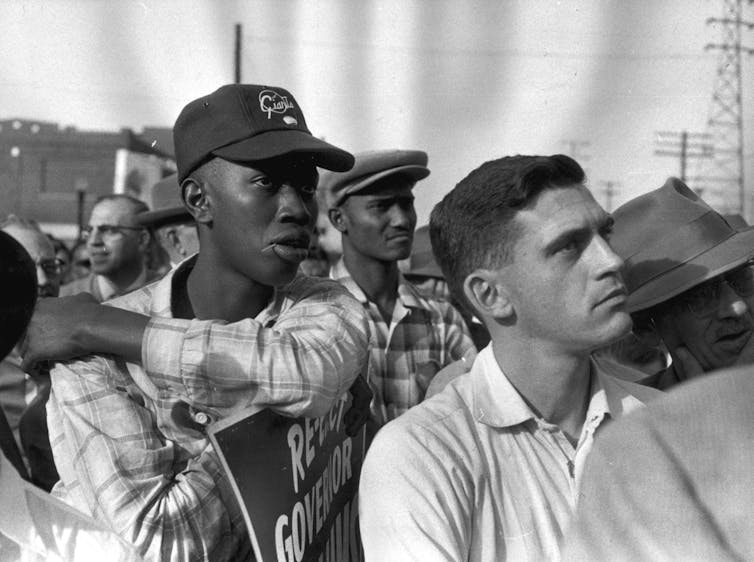

Ban Martin/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Crises distort forecasts

The Times' 1956 experiment represents a rare case study within the appeal and limitations of in-depth, interview-based reporting as a way for measuring public opinion in presidential campaigns, particularly when dramatic international events occur shortly before the election.

This was the case in 1956 when the Egyptian government seized the Suez Canal and caused this to occur military intervention by Israeli, British and French forces – a response that Eisenhower regretted. At concerning the same time, Soviet tanks were ordered to Hungary Crush an rebellion against communist rule and install a Moscow-compliant regime.

The international crises could have increased the margin of victory for Eisenhower, an Army general in World War II, in a “rally for the president” effect.

In any case, it was an election failure that inspired the Times' campaign reporting experiment.

Eight years ago, in 1948The polls, the press, and pundits predicted that Republican Thomas E. Dewey would oust Democrat Harry S. Truman, who had grow to be president after the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945.

But because of a vigorous, cross-country campaign Truman defeated Dewey and two minor party candidates win.

The leading national pollsters of the time—George Gallup, Archibald Crossley, and Elmo Roper— Everyone predicted Dewey's easy victory. Roper announced in early September 1948 that Dewey was to this point ahead that he would stop publishing survey results. Dewey, Roper said, would win.with a giant lead.”

Truman, who predicted that pollsters “red-facedThe day after the election, there have been 28 states and 303 electoral votes. Be Leading strategy to defeating Deweywho won 16 states and 189 electoral votes was 4.5 percentage points. J. Strom Thurmond of the segregationist Dixiecrat Party carried 4 Deep South states and 39 electoral votes.

Not tied to the “arithmetic of polls”.

Not surprisingly, Gallup, Crossley, and Roper were extremely cautious in assessing the 1952 presidential campaign, claiming at the tip of the campaign that any candidate could win.

They said Eisenhower looked as if it would have a narrow lead, but Stevenson was closing in quickly. Or just like the Times said in reporting a few public meeting of pollsters shortly before the election: “The pollsters gave…Eisenhower, the Republican nominee, a slight lead in the popular vote, but this was their dilemma: How quickly will…Stevenson, the Democratic nominee, catch up?” “

The equivocation didn’t profit the pollsters. None of them expected Eisenhower's overwhelming victory – a landslide victory in 39 states.

The Times didn’t editorially reprimand the pollsters for his or her failure in 1952, however the paper's editors did, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Max Frankel wrote in his memoirsHe has “lost confidence in the polls”.

To cover the 1956 presidential election, the Times emphasized public opinion polls and as an alternative focused by itself intensive on-the-ground coverage, specializing in states where the presidential race was prone to be closely contested.

Bert Hardy/Image article/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Frankelwho rose to grow to be executive editor of the Times, recalled being pulled away from the newsroom in 1956 and knocking on doors “to gather voter sentiment.” I drove through strange counties in Milwaukee and Austin, Texas, Arlington, Virginia, and St. Joseph, Missouri, passing notes to a colleague on one among the reporting teams.

The teams typically spent three days in a state, conducting interviews “with political scientists and police officers, political leaders and bartenders, workers, housewives and farmers,” the paper said.

The Times described its grassroots reporting as “Surveys“, although they weren’t quantitative samples.

“Team members found value in not being bound by the arithmetic of polls,” wrote one among the participants, Donald D. Janson, in a post-election review for the Nieman Reports, a journalism industry publication.

“The scope and depth of the effort represented a new path in journalism,” Janson said.

The process was impressionistic, even idiosyncratic. “Every reporter,” Janson wrote, “had the freedom to assess the reliability of every response, from both politicians and voters.”

The Times published 36 state-specific area code reportsincluding nine based on follow-up visits by reporters to states where a very close result was expected.

In his Final report Two days before the election, the Times said it “seemed doubtful” whether Eisenhower's lead could be “as large as it was in 1952.” Actually, Eisenhower's victory in 1956 far exceeded that of 1952; In the rematch, he beat Stevenson by greater than 9.5 million votes.

The times admitted in an article after the election that the team-based reporting “failed to anticipate the magnitude of the president’s victory,” which she attributed to the Suez crisis and unrest in Hungary. The crises, the Times said, “apparently provided the final impetus for the Eisenhower landslide.”

No antidote to bad polls

The shoe leather reporting experiment of 1956 was not a powerful success. “It was felt,” Janson later wrote, “that the Times should stick to reporting trends and leave the forecasts to the pollsters.”

Pre-election polls from Gallup and Roper in 1956 accurately predicted Eisenhower's victory but exaggerated the president's majority vote. Eisenhower won by 15 points; Gallup and Roper estimated his margin of victory at 19 points. By 1956, Crossley had sold his company and retired from campaigning.

Roper said he was “personally pleased” with the result but was hesitant to make “any bows about perfect accuracy.”

Given the unreliability of pre-election polls within the late Forties and early Fifties, the Times had every reason to experiment with the seek for a more accurate understanding of public opinion. But as the outcomes of the 1956 election showed, shoe coverage was no antidote to erratic polls.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply