Long-term high concentrations of ultrafine particles in New York State neighborhoods are related to higher numbers of deaths. That's that Key finding of our recent researchpublished within the Journal of Hazardous Materials.

Our study shows that top concentrations of ultrafine particles within the atmosphere over long periods of time are significantly related to a rise in non-accidental deaths, particularly from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.

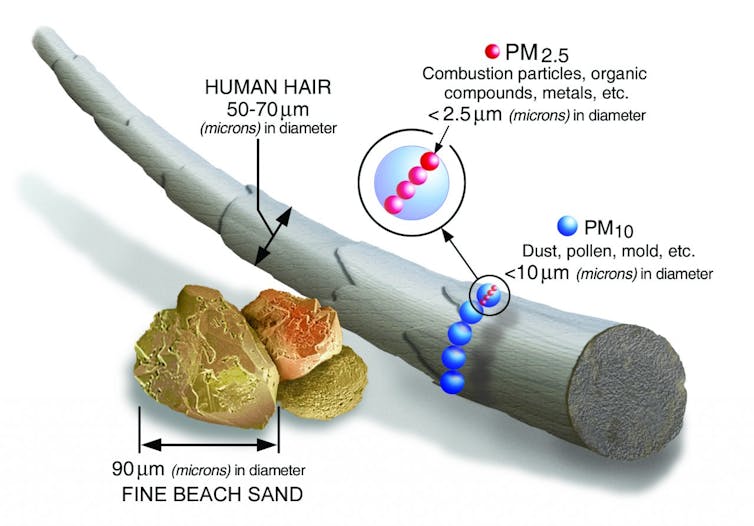

Ultrafine particles are aerosols with a diameter of lower than 0.1 micrometers, or 100 nanometers – about one-thousandth the width of a human hair. Due to their small size, they could be easily inhaled into the distal branches of the lungs, quickly absorbed into the bloodstream, and even go through organ barriers.

We also found that certain underserved populations, including Hispanics, non-Hispanic Blacks, children under 5, older adults and non-New York residents, are more liable to the harmful effects of ultrafine particles. The disparities uncovered by our study highlight the necessity for public health authorities to concentrate on and protect high-risk groups.

We quantified the long-term health effects of exposure to those pollutants by combining mortality data from vital records in New York State and using a model that tracks how particles move and alter within the air.

Why it matters

Air pollution is now the primary priority second commonest risk factor for deathThis accounts for about 8.1 million deaths worldwide and about 600,000 deaths within the United States in 2021.

Most air pollution standards and regulations apply focused on larger particlescorresponding to PM2.5 – which incorporates organic compounds and metal particles – and PM10, a category that features dust, pollen and mold.

In comparison, ultrafine particles are typically much larger and have a much larger surface area to volume ratio, allowing them to move significant amounts of hazardous metals and organic compounds. In addition, resulting from their smaller size, ultrafine particles can follow the airflow and travel deep into the lungs when inhaled. These unique properties make ultrafine particles particularly dangerous and result in various harmful health problems.

Despite this understanding Ultrafine particles remain largely unregulatedwhile larger particles are regulated under the regulation National air quality standards.

Due to their unique properties, ultrafine particles require additional, tailored attention.

US Environmental Protection Agency

Ultrafine particles come from each natural sources and human activities – primarily through combustion processes corresponding to motorized vehicles, power plants, wood burning and forest fires. A big proportion consists of ultrafine particles are brought on by chemical reactions within the atmosphere with acidic gases Combustion of fossil fuels and ammonia from agricultural and municipal waste.

As cities proceed to grow and concrete populations grow, people's exposure to those harmful particles is more likely to increase. Both PM2.5 and ultrafine particles come from similar sources and may also arise from chemical reactions within the atmosphere, but their trends differ.

Thanks to air quality regulations, PM2.5 mass has declined in lots of places, including New York. However, recent research suggests that the variety of ultrafine particles is just not decreasing have increased since 2017.

What is just not yet known

There are currently no large-scale monitoring sites within the United States dedicated to tracking ultrafine particles within the environment. This limits the power of researchers like us to know the extent of exposure to ultrafine particles and their impact on public health.

Furthermore, the precise biological mechanisms by which ultrafine particles cause damage aren’t yet fully understood. Increasing research suggests that ultrafine particles can impair heart functionresulting in hardening of the arteries, pneumonia and systemic inflammation.

To date, there have been few studies examining mortality rates related to exposure to ultrafine particles by demographics and seasonality. By understanding which groups are most affected by exposure to ultrafine particles, interventions could be tailored more effectively to cut back risks and protect those that are disproportionately affected. Our study, funded by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, helps fill these critical knowledge gaps.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply