In probably the most haunting scenes from Stephen King's 1975 novel “Salem's property“A gravedigger named Mike Ryerson runs to bury the coffin of an area boy named Danny Glick. As night approaches, Mike is struck by a disturbing thought: Danny was buried along with his eyes open. Worse, Mike feels Danny taking a look at him through the closed coffin.

A mania comes over Mike. Prayers run through his mind – “how things like this happen for no good reason.” Then more troubling thoughts arise: “Now I'm bringing you rotten meat and stinking meat.” Mike jumps into the opening he dug and shovels indignant earth from the coffin. The reader knows what he’ll do next, but what he shouldn't do: Mike will open the coffin and free what has turn into of Danny.

Enter the whipping poor will. Some of them, King writes, “had begun to raise their shrill call,” the demand for violence that offers the species its name: whip poverty.

This isn't the primary time pauper whips have appeared in “Salem's Lot,” neither is it the last time King will invoke them in his work. But despite their importance to King, pauper whippers never appear in film and tv adaptations of “Salem's Lot.”

Released on October 3, 2024, the newest adaptation of “Salem's property” incorporates birdsong, but barely uses them. Here and there a crow or a blue jay calls. Sparrowlike chirps pepper scenes at night. And when Mike digs up the undead Danny, he becomes less threatening Call of a barred owl replaced that of the poor with whips.

As a cultural sociologist I'm writing a book about Eastern whip poorwillI don't care about this omission since it reflects an unfaithful recreation of King's novel. Rather, I view the extinction of the Salem's Lot paupers as a symptom of broader ecological changes wherein species loss can be linked to cultural loss.

The horror of the night

At least in Washington Irving's “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” The Call of the whip poora member of the nocturnal nightjar family, haunted American literature.

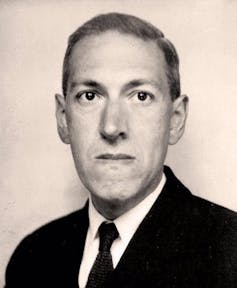

Perhaps essentially the most famous poor-whip artists of American horror movies appear in HP Lovecraft's novella “The Dunwich Horror.” Lovecraft refers back to the species nearly two dozen times in his story, with the birds continuously appearing across the deaths of the Whateley family, who live within the fictional town of Dunwich, Massachusetts.

By behaving in ways in which real poor people would never do, Dunwich's nightjars symbolize the fear that the Whateleys unleash on the townspeople. The birds also act as psychopomps: Beings who lead the souls of the newly dead into the afterlife.

Wikimedia Commons

Dunwich's poor children stay on the town until Halloween – “unnaturally late,” Lovecraft writes – and sing in tune with the dying breaths of Whateleys. (In fact, most poor people leave the Northeast by the top of September, and they typically don't coordinate their singing.) But although the poor individuals are crucial to the plot of “The Dunwich Horror,” one other commonality is Owl, here a Virginia -Uhu, replacing Whip-Poor-Wills within the 1970 film adaptation Lovecraft's story.

King also uses his poor will to great effect. In “Jerusalem's plumb line“, the short story that King later published as a prelude to “Salem's Lot,” haunts Armenians within the Maine town. And in his 1989 novel “The dark half“” King refers back to the whip poor lore as “psychopomps.”

Lovecraft's and King's fictional poor-wild-whip draw on widespread indigenous, European, and American beliefs in regards to the species. The singing of a whip-poor whip near the home was a very ominous sign and frequently meant that death would soon befall someone in the home would. A Article from 1892 within the American Journal of Folklore documents this belief in King's home state of Maine. It also offers a probable apocryphal story as evidence: “A whippoorwill sang repeatedly at a back door; Eventually the woman’s son was brought home dead and the body was brought into the house through the back door.”

Birds and faith disappear

For many of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, lore in regards to the poor will of the whip circulated amongst individuals who encountered the bird. Outside the world of folklore studies, passing mention of bad omens may be present in the book's natural writings Henry David Thoreau And Susan Fenimore Cooperalthough nobody believed these superstitions. Local newspapers continued to share stories in regards to the birds with their readers well into the twentieth century.

But because the species' erasure from horror suggests, the broader cultural familiarity with whip-poor-will has atrophied. In one exception: “Chapelwaite“, a 2021 television series based on King's “Jerusalem's Lot,” the characters explicitly discuss the birds' behavior in order that viewers understand the reference.

The cultural extinction of the whip poor reflects the actual decline of the species. Conservationists imagine eastern whippoor populations are being affected declined by about 70% for the reason that Seventies. This decline is probably going resulting in what naturalist Robert Michael Pyle called “Extinction of experience.” Pyle suggests that when a species declines, people lose the chance to come across it in local landscapes and are less prone to be aware of it in any respect.

Such declines too cause social and cultural losses. This is most evident when a species goes extinct. Consider the passenger pigeon. As writer Jennifer Price shows in her book: “Flight tickets“The lives of Americans were once tied to the species. When huge flocks of passenger pigeons arrived, communities gathered to hunt the birds that were once a staple within the American food regimen. Today, nonetheless, the species is remembered almost exclusively as an emblem of human-caused extinction.

Bettman/Getty Images

The decline in bird species can be changing people's relationship with the environment. In the United Kingdom, for instance Decline in house sparrows robs landscapes of the beloved sights and sounds of a once ubiquitous species. The lack of Cuckoosmeanwhile, means spring arrives in Britain without its iconic song.

Beyond cultures of loss

I feel we’re seeing similar cultural shifts amongst paupers-savages. Their absence from the adaptations of King's works reflects their absence from each the landscape and other people's lives. But although loss and grief rightly characterize many individuals's relationships with those in need and other perishing species. I need to advocate for hope.

On the one hand, there may be reason to be hopeful about the potential of preservation: whip poor wills appear to achieve this respond well to forest management practices which create diverse forests with a mixture of younger and older trees. Many places where marsh birds breed have energetic conservation plans in place to support the birds and other species that share their habitat.

Victims of poverty attributable to culture haven’t died out either.

After all, readers still find their solution to the works of Lovecraft and King. These and other lasting references to the species offer people the chance to return to the bird – and to the importance of the species to all who cared for it.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply