When I began my research Samuel George Morton skull collectionOne day a librarian leaned over my laptop to share some knowledge. “According to legend,” she said, “John James Audubon really collected the skulls that Morton claimed as his own.” Her voice was quieter in order to not disturb the opposite scholars within the quiet archive.

As I continued my work, I discovered no evidence to support their whispered claim. Audubon had collected human skulls, several of which he gave to Morton. But birds and ornithology remained Audubon's passion.

Still, the librarian's offhand comment proved useful – a touchstone of sorts that continues to remind me of the controversy and confusion that has long surrounded the Morton Collection.

Morton was a physician and naturalist who lived in Philadelphia from 1799 until the top of his life in 1851. A Lecture he gave to aspiring doctors from the Philadelphia Association for Medical Instruction explained the explanations for his cranial urge:

“I started studying ethnology in 1830; When I had the chance to offer an introductory lecture on anatomy this 12 months, the thought occurred to me of illustrating the difference in skull shape seen within the five major races of humans… As I used to be in search of the materials for my proposed lecture, I discovered it. To my surprise, you couldn't buy it or rent it.”

He then acquired nearly 1,000 human skulls.

Morton used these skulls to advertise understanding that racial differences are natural, easily categorizable and classifiable. Big-brained “Caucasians,” he argued within the 1839 publication “Crania Americana“were far superior to the small-skulled American Indians and even the smaller-skulled black Africans. Many later scholars have since done this thoroughly exposed his ideas.

Certainly the condemnation of Morton is as scientific racist is justified. But I believe this attitude paints the person as a caricature and presents his conclusions as a foregone conclusion. It offers little insight into his life and the complicated, interesting times wherein he lived, as I detail in my book.Becoming an Object: The Sociopolitics of the Samuel George Morton Cranial Collection.”

My research shows that studies of skulls and disease conducted by Morton and his medical and scientific colleagues contributed to an understanding of U.S. citizenship that valued whiteness, Christianity, and heroic masculinity defined by violence. It is a exclusionary idea of what it means to be American that continues to this present day.

But at the identical time, the gathering is an unintended testament to the range of the U.S. population at a turbulent moment within the country's history.

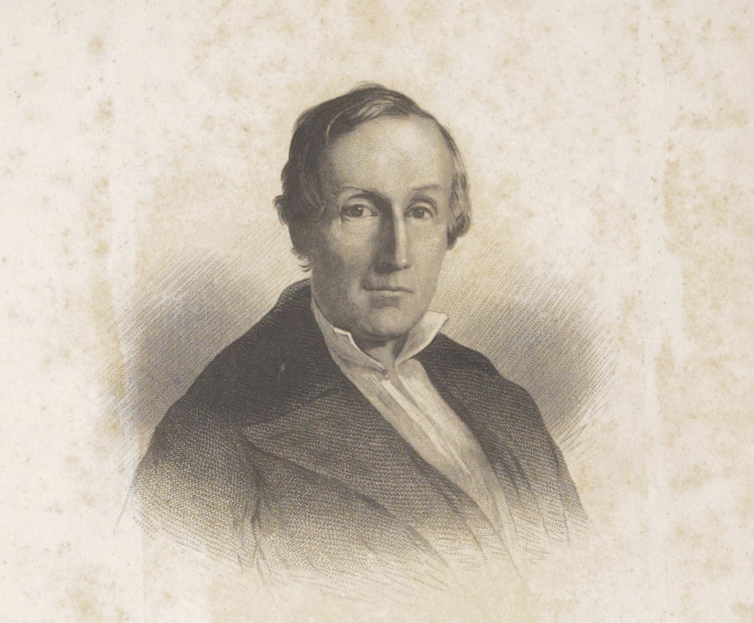

“Reminiscences of the Life and Scholarly Work of Samuel George Morton” by Henry S. Patterson, CC BY

Men of Science and Medicine

As a bioarchaeologist who studied this Morton Collection For a few years I actually have been trying to raised understand the social, political and ideological circumstances that led to its creation. Through my work—analyzing archival sources, including letters, laws, maps, and medical treatises, in addition to the skulls themselves—I learned that over the course of his life, Morton built knowledgeable network with far-reaching tentacles.

He had loads of assist in assembling the gathering of skulls that bears his name.

The doctor socialized with medical colleagues – a lot of whom, like him, received degrees from the University of Pennsylvania – gentleman planters, slave owners, naturalists, amateur paleontologists, foreign diplomats and military officers. Aside from the skilled differences, they were predominantly white, Christian men with reasonable means.

Their interactions took place at a pivotal moment in American history, the interlude between the nation's revolutionary consolidation and its violent civil disintegration.

Over this time, Morton and his colleagues have advanced biomedical interventions and scientific standards to treat patients more effectively. They have launched public health initiatives over time Epidemics. They have established themselves Hospitals and medical schools. And they did so within the service of the nation.

However, not all lives were considered worthy of those men's care. Men of science and medicine could have made life possible for a lot of, but additionally they allowed others to die. In “grow to be an object“I follow how they portrayed certain populations as biologically inferior; Diseases were related to non-white people, female anatomy was pathologized, and poverty was viewed as inherited.

From human to specimen

Such representations made it easier for Morton and his colleagues to manage the bodies of those groups, rationalize their deaths, and collect their skulls with casual cruelty from dissection tables in almshouses, looted cemeteries, and so forth Battlefields plagued by bodies. That is, a big proportion of the skulls in Morton's collections didn’t come from ancient graves, but were those of recently living people.

It isn’t any coincidence that Morton began his scientific research the identical 12 months that Andrew Jackson signed the treaty Indian Removal Act of 1830. Men of science and medicine benefited from the expansionist policies, violent war conflicts, and indigenous displacement that underpinned them Manifest Destiny.

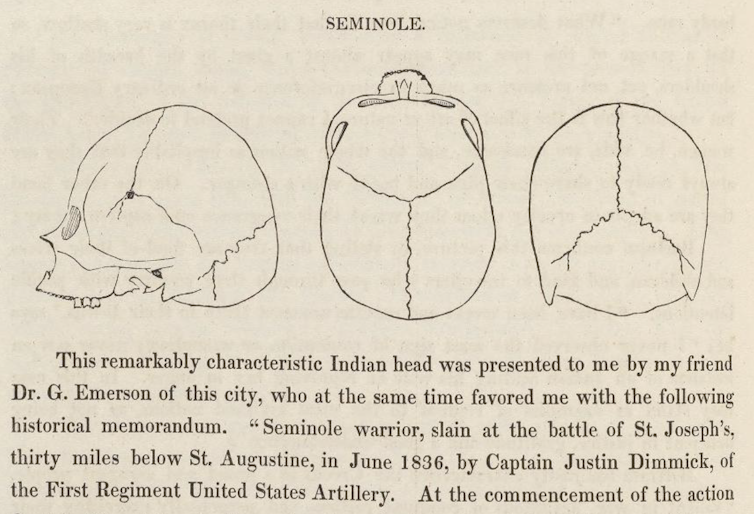

Crania Americana by Samuel George Morton, CC BY

The collection reveals these acts of nation constructing as Necropolitical strategies – Techniques utilized by sovereign powers to destroy or erase from the national consciousness certain, often already vulnerable, populations. These skulls bear witness to precarious existences, premature deaths and trauma experienced from cradle to death.

In the precise case of Native Americans Skeletal analyzes reveal the severe effects of US military campaigns and compelled evictions. Native skulls, which Morton described as “warriors,” show evidence of unhealed fractures and gunshot wounds. Children's skulls bear the marks of compromised health; Such pathology and its young age at death are evidence of long-term malnutrition, poverty, deprivation or stress.

To effectively transform subjects into objects—people into specimens—collected skulls were housed within the institutional spaces of medical school lecture halls and in museum storage cabinets.

There, Morton first numbered them consecutively. These numbers, together with details about race, gender, age, “idiocy” or “criminality,” cranial capability, and origins, were written on skulls and recorded in catalogs. Very rarely was the person's name recorded. When used as a teaching tool, Morton drilled holes to hold the skulls for display and labeled them with the names of skeletal elements and features.

As dehumanizing as this process was, the Morton Collection accommodates evidence of resilience and heterogeneous lives. There are traces of individuals with multiracial backgrounds corresponding to black Indians. Some people may have modified gender to address dire conditions or to adapt to social norms, corresponding to: local beloved womenwho were lively in warfare and political life.

Pamela L. Geller

What these bones mean today

As anthropologists now realize, this is finished by returning the stays of the people within the Morton Collection to their descendants. amongst other sorts of reparationsthat current practitioners can begin to atone for the sins of their mental ancestors. In fact, all institutions that house legacy collections must grapple with this issue.

There are other beneficial lessons—about diversity and suffering—that the Morton Collection must convey in today's interesting times.

The collection shows that American body politic has at all times been diverse, despite the efforts of men like Morton and his colleagues to erase it. Piecing together the stories of past, disenfranchised lives—and acknowledging the silences which have made them difficult to concretize—counters the white nationalism and xenophobia of the past and their current resurgence.

In my opinion, the gathering also urges the rejection of violence, casual cruelty and opportunism as admirable attributes of masculinity. Valuing men who embody these qualities has never done America any good. Particularly within the mid-Nineteenth century, when Morton amassed skulls, it led to a nation divided and hardened to suffering. an unbelievable variety of deaths and the increasing fragility of democracy.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply