“7 Mile + Livernois” on the Detroit Institute of Arts celebrates Detroit as a spot for Black women to live and create by highlighting each the work of featured artist Tiff Massey and the community from which she comes.

The exhibition draws attention to how Detroit is represented within the national – and even global – imagination.

As an art historian specializing in modern and contemporary art of the African diasporaI discovered the exhibition absolutely fascinating. I appreciate the way in which the show acknowledges Black people's desire for belonging and self-expression. I also admire how the show empowers and inspires everyone who attends it.

Named after a street of black fashion

Massey's exhibition is known as after her childhood neighborhood, which can be crucial historical, cultural and economic center of Black Detroit.

The area near the intersection of Seven Mile Road and Livernois Avenue, popularly called the Avenue of Fashion due to its many clothiers, was until then an epicenter of black commerce the Detroit riot of 1967 sent shoppers to suburban malls.

The Detroit Institute of Arts

A Resurgence of entrepreneurship And a rise in state funding revitalize the world by removing abandoned buildings and supporting redevelopment. This is a component of a citywide trend of accelerating investment and population growth over the past decade or so.

The exhibition poignantly examines the good varieties of previous generations and the way Black Detroiters today draw on this tradition of their clothes and accessories.

Throughout history, dressing “best on Sunday” has been a way of dressing for a lot of African diaspora communities assert one's own humanity and dignity. Without query, this exhibition honors the importance of this cultural practice.

Monumentalize on a regular basis life

The exhibition features recent works in addition to two latest sculptures by Massey commissioned by the Detroit Institute of Art. Her latest work shall be juxtaposed with pieces from the museum's everlasting collection.

At the doorway to the exhibition, cubic shapes made from silver metal are connected together and in the course of the outer wall of the galleries in a sculpture called “ “Whatupdoe” (2024)which can be a well-liked greeting amongst Detroiters. Even larger cubic shapes emerge from the wall in each square and rectangular shapes and rest on the ground. The sculpture resembles a press release necklace and takes up much of the gallery space.

Detroit Institute of Art

The change in scale gives it architectural flair, evoking the buildings and houses that line the streets of Detroit and the numerous individuals who live each inside and outdoors the buildings. The connected connections symbolize the ties that connect the several parts of town and connect generations of individuals to town.

We have a good time the built environment

“I Got Bricks” (2016) consists of serial collections of metal blocks shaped like gemstones set in jewelry. The six groups of glittering panels are harking back to the shapes of bricks used to construct architectural structures within the early to mid-Twentieth century, but are presented in geometric and varied arrangements.

The work again speaks to the thought of seeing oneself within the built environment. “I Got Bricks” suggests that neighborhoods once viewed disparagingly might be seen as places of beauty that reflect the history of many African American families who’ve overcome great adversity and lived extraordinary lives.

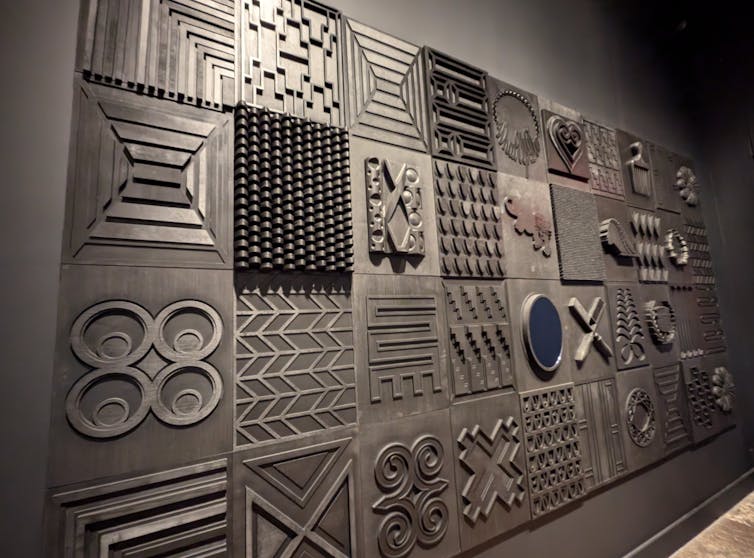

“Quilt Code 6 (All Black Everything)” (2023) is a wonderful, black-painted picket installation that comes with iconography and design motifs from town, in addition to the artist’s archive. An Afro comb, the Cadillac logo, a pair of hot combs, the Black Panther Party logo, an Adinkra symboland design motifs on constructing facades are a few of the images utilized in this work.

The Conversation/Monica Williams, CC BY-ND

It is situated near a mid-century sculptor, Louise Nevelson's “Homage to the World” (1966)which can be painted black but features debris from the streets of New York City. This juxtaposition illustrates how each works use similar compositions to convey two different worldviews: certainly one of an African American woman born within the late Twentieth century and the opposite of a European American woman born within the late nineteenth century .

“I have bundles and flew out (green)” (2023) is the same installation featuring a series of green and yellow hairpieces of various texture and magnificence displayed on a black coloured background. The theme of artificiality involves mind as an integral a part of black women's beauty rituals.

The Conversation/Monica Williams

The items brought in “I Remember the Time Long Ago” (2023) And “Baby Bling” (2023) are easy to acknowledge for a lot of black women and other women of color, especially those that were children within the Nineteen Seventies and Nineteen Eighties.

The former features hair clips while the latter features hair ties with balls on each ends. The 11 enlarged objects in each works are painted a surprising red and arranged horizontally, literally making an enormous contribution to how black girls present themselves to the world.

These nostalgic works are juxtaposed with minimalist artists Donald Judds rendered vertically “Stack” (1969)which uses a series of green rectangular shapes to evoke modernist architecture.

Making art within the Motor City

Metalsmithing is closely linked to Detroit's reign as an industrial mecca within the early Twentieth century. During this time town won a workforce of African Americans fleeing the South in addition to immigrants Europe, the Middle East and even Latin America And the Caribbean.

In “Fulani” (2021), “39 Reasons Why I Don’t Play” (2018) and “Everyday arsenal” (2018), Massey skillfully reveals how the on a regular basis objects of self-beautification celebrated within the exhibition have a history with the metalsmithing of the automotive industry within the Motor City.

Emily Costello/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

The galleries stuffed with Massey's works invite viewers to pay closer attention to the on a regular basis objects and the built environment that surround us.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply