The Lex talionis of the Bible – “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth“Hand for hand, foot for foot” (Exodus 21:24-27) – has captured the human imagination for millennia. This idea of justice serves as a model for ensuring justice in cases of bodily harm.

Thanks to the work of Linguists, historian, Archaeologists And AnthropologistsResearchers know lots about how different body parts are valued in small and enormous societies from precedent days to the current.

But where did such laws come from?

According to at least one school of thought, Laws are cultural constructions This signifies that they vary depending on culture and historical period, adapting to local customs and social practices. By this logic, personal injury laws would differ significantly between cultures.

Our latest study explored one other possibility – that non-public injury laws are rooted in something universal human nature: shared intuitions concerning the value of body parts.

Do people from different cultures and throughout history agree about which body parts are kind of precious? So far, nobody has systematically examined whether body parts are valued equally across space, time and legal expertise – that’s, between laypeople and legislators.

We are Psychologists who study assessment processes And social interactions. In previous research, we found regularities in the way in which people evaluate various things illegal acts, personal characteristics, Friends And Groceries. The body is probably an individual's most precious asset and on this study we analyzed how people value its different parts. We examined connections between intuitions concerning the value of body parts and laws about bodily harm.

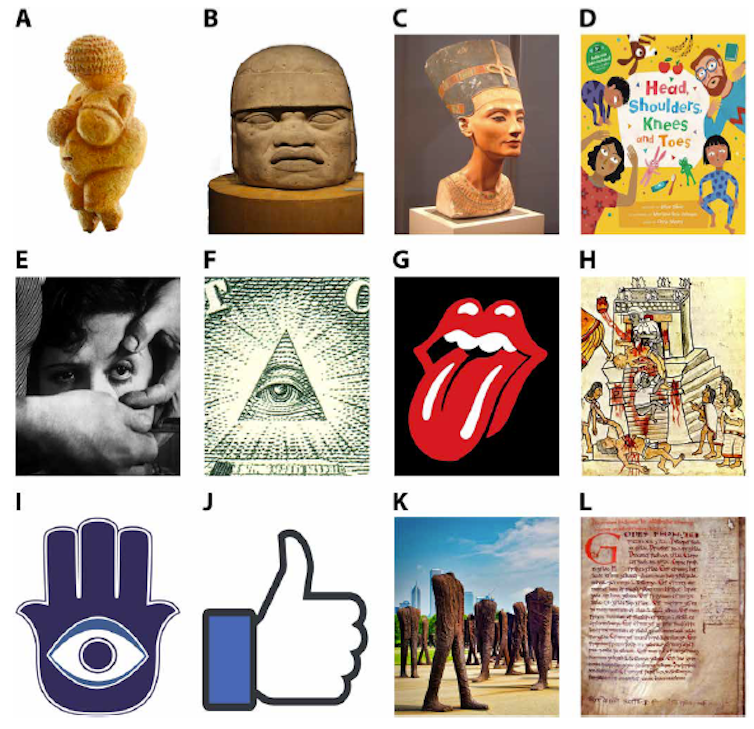

(A) Body: Venus of Willendorf, Austria, roughly 29,500 years ago, Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria. Photo by M. Kabel (multiple license with GFDL and Creative Commons) (B) Head: Olmec colossal head, San Lorenzo, Veracruz, Mexico, 1200 to 600 BC. BC, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico. (C) Torso: Bust of Nefertiti, Egypt, 14th century BC. BC, Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany. (D) Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes: Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes: Children's Song, illustrated by MR Johnson, written by S. Silver, published by Barefoot Books. (E) Eye: Film still from L. Buñuel's “An Andalusian Dog” (67), photo by A. Duverger and J. Berliet. (F) Eye: Eye on the back of the $1 bill. (G) Mouth: Rolling Stones logo designed by J. Pasche, The Rolling Stones. Shutterstock. (H) Heart: Aztec Codex Magliabechiano, circa mid-Sixteenth century, National Central Library, Florence, Italy. (I) Hand and Eye: Hamsa amulet against the evil eye, North Africa and the Middle East. (J) Thumb: Facebook Like button. Wikimedia Commons. (K) Legs: Agora, by M. Abakanowicz, Grant Park, Chicago, photo by R. Mines. (L) Opening page of the Law of Æthelberht, Kingdom of Kent, circa 600 AD, Kent County Archives, Maidstone, England., CC BY-NC

How essential is a body part or its function?

We began with a straightforward statement: Different body parts and functions have different effects on an individual's probabilities of survival and thriving. Life and not using a toe is annoying. But life and not using a head is unattainable. Could people intuitively understand that different body parts have different values?

Knowing the worth of body parts gives you a bonus. For example, in the event you or a loved one have suffered multiple injuries, chances are you’ll decide to treat the most precious body part first or devote a bigger portion of limited resources to treatment.

This knowledge could also play a job in negotiations when one person has hurt one other. If person A injures person B, B or B's family can claim damages from A or A's family. This practice occurs all around the world: among the many MesopotamiansThe Chinese throughout the Tang DynastyThe Enga of Papua New GuineaThe Nuer in SudanThe Montenegrins and lots of others. The Anglo-Saxon word “wergild“, meaning “human price,” now generally refers back to the practice of paying for body parts.

mikroman6/Moment via Getty Images

But how much compensation is fair? Too few claims result in losses, while too high claims result in retaliation. To walk the nice line between the 2, victims would demand compensation in Goldilocks fashion: excellent, based on the consensus value that victims, perpetrators, and third parties in the neighborhood place on the body part in query.

This Goldilocks principle is clearly reflected in the precise proportionality of the Lex talionis – “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”. Other laws prescribe precise values for various body parts, but in the shape of cash or other goods. For example this Codex of Ur-Nammuwritten 4,100 years ago in ancient Nippur, now Iraq, says that a person must pay 40 shekels of silver if he cuts off one other's nose, but only 2 shekels if he knocks out one other's tooth.

Testing the concept across cultures and time

If people have intuitive knowledge of the values of various body parts, could this information underpin body harm laws in numerous cultures and historical periods?

To test this hypothesis, we conducted a study with 614 people from the United States and India. Participants read descriptions of assorted body parts, similar to “an arm,” “a foot,” “the nose,” “an eye,” and “a molar.” We selected these body parts because they seem in jurisdictions from five different cultures and historical periods that we examined: the Æthelberht's law from Kent, England, in 600 AD, the Guta team from Gotland, Sweden, in 1220 AD and modern employees' compensation laws from the United States, South Korea and the United Arab Emirates.

Participants answered a matter about each body part they were shown. We asked some people how difficult it might be for them to operate in every day life in the event that they lost various body parts in an accident. We asked others to assume themselves as legislators and determine how much compensation an worker should receive if that person lost various body parts in an industrial accident. Still others, we asked to estimate how offended one other person could be if the participant damaged various parts of the opposite person's body. Although these questions are different, they’re all based on assessing the worth of various body parts.

To determine whether untrained intuitions underlie the laws, we didn’t include individuals with a school education in medicine or law.

We then analyzed whether participants' intuitions were consistent with the legal compensation.

Our findings were noticeable. The values that each laypeople and legislators attached to body parts were largely consistent. The higher American laypeople valued a specific body part, the more precious that body part also appeared to Indian laypeople, American, Korean and Emirati legislators, King Æthelberht and the authors of the Guta Lag. For example, laypeople and legislators agree in all cultures and across centuries generally agree that the index finger is more precious than the ring finger and that a watch is more precious than an ear.

But do people evaluate body parts accurately and in a way that corresponds to their actual functionality? There is a few evidence that that is the case. For example, laypeople and legislators consider the lack of a single part to be less serious than the lack of multiples of that part. Furthermore, laypeople and legislators perceive the lack of an element as less serious than the lack of the entire; Losing a thumb is less serious than losing a hand, and losing a hand is less serious than losing an arm.

Further evidence of accuracy may be obtained from ancient laws. Linguist Lisi Oliver, for instance, notes that in barbaric Europe “there are wounds that can lead to permanent incapacity or disability.” will likely be subject to higher fines than those that could eventually heal.”

Although people generally agree that some body parts are more valued than others, there are some There could also be noticeable differences. For example, eyesight could be more essential to someone who makes a living as a hunter than as a shaman. The local environment and culture could also play a job. For example, upper body strength could be particularly essential in violent areas where one must defend against attacks. These differences still have to be investigated.

H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock via Getty Images

Morality and law, across time and space

Much of what is taken into account moral or immoral, legal or illegal, varies from place to put. Drinking alcohol, eating meat, and marrying cousins, for instance, were condemned or encouraged in a different way at different times and places.

But current research has also shown that in some areas there may be much greater moral and legal consensus about what’s improper, across cultures and even across millennia. Misbehavior—arson, theft, fraud, trespassing, and disorderly conduct—seems to supply morals and associated laws which might be similar across times and places. Personal injury laws also appear to fit into this category of ethical or legal universals.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply