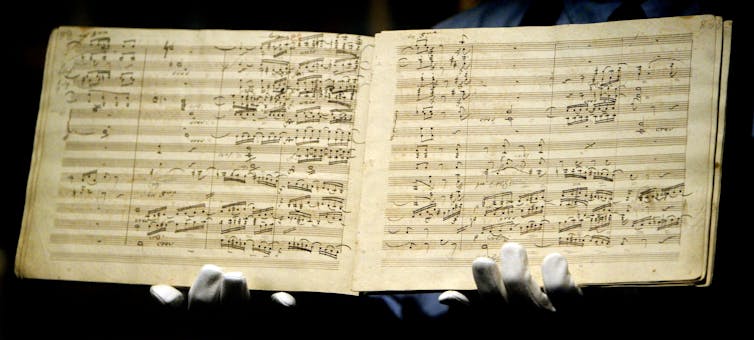

On May 7, 1824, Ludwig van Beethoven's Ninth Symphony was premiered in Vienna, Austria. On the occasion of its 2 hundredth anniversary, much has been made from this groundbreaking achievement by a composer frequently heralded as the best master of all time.

In an essay for the New York Times Conductor Daniel Barenboim wrote that Beethoven was “the master of bringing emotion and intellect together.”

In one other evaluation, music historian Ted Olson wrote that the Ninth was “the pinnacle of Western classical music.”

There is no doubt that Beethoven's Ninth Symphony is a significant work with “global appeal,” as my colleague Olson put it. I admit that I even have a soft spot for this piece. As a cellistI played it twice, once at Carnegie Hall and once while on tour in Asia.

However, I never liked the glorification of Beethoven.

Beethoven backlash

Four years ago I did published a blog post himself under the heading “Beethoven was an above-average composer: let’s leave it at that.”

I had grown bored with the thought of the composer's “genius” and the way we were all taught to position him on a sacred hill because the “great master of the Western canon.”

To say the least, my blog post caused quite a stir.

In “Classical Music’s Suicide Pact (Part 1)” Heather MacDonalda conservative fellow on the Manhattan Institute, wrote that my blog post was a “Beethoven defeat” and that I had “Whiteness within the brain.”

Professor of linguistics John McWhorter even went thus far as to say that I believe Beethoven was “fetishized by the white establishment.”

Conservative commentators defending certainly one of their heroes is nothing recent, however the backlash to my easy reinterpretation of the composer was distorted beyond recognition.

Redefining “The Master.”

My intention was to redefine Beethoven’s greatness within the context of historical ideals white And Patriarchy. I believed then – as I do now – that if Americans could recognize that our music and our music education are deeply rooted in these two ideologies, then we could recognize that Beethoven, actually a very good composer, was simply certainly one of many.

Ian Waldie/Getty Images

When Beethoven is known as “one of the greatest” composers or “the greatest” composer, those that make this claim achieve this without knowing nearly all of the music that has been created over the centuries.

As I wrote on the time, Beethoven was definitely above average, but “to say he was more is to dismiss 99.9% of the world music written 200 years ago, which would be unscientific and academically irresponsible.”

To understand his reverence, one must imagine in narratives of Western greatness and exceptionalism: that one of the best musical works on our planet were produced by a number of people from a number of countries, and people people were, after all, each white and white male.

To further confuse matters, conservative musicologists normally ask the identical query: “Well, Phil, if not Beethoven, then who?”

However, this query is most frequently asked in bad faith, as there isn’t a acceptable answer for many who defend the established norms of the musical tradition. Whoever is chosen – and I could name many – the questioner can all the time find fault and be dismissive.

For me, it's all about whiteness and masculinity, their influence on the creation of musical foundations and who gets to define the abstract concept of greatness. The point shouldn’t be necessarily to search out alternative composers who could never live as much as the arbitrary and unrealistic standards that Beethoven supposedly embodies.

To be clear, this shouldn’t be about “cancelling” Beethoven. Instead, it’s about recognizing that there have been countless others who were no less great than these celebrated white male heroes.

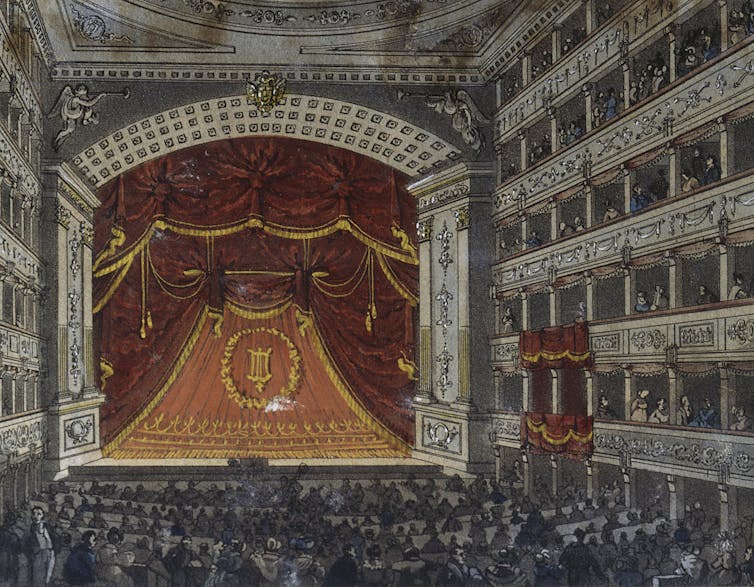

DEA/A. DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini via Getty Images

“Cancel culture” is most frequently utilized by the fitting as a cudgel against those like me who wish to have adult conversations about our troubled racist past.

And there isn’t a doubt concerning the anti-Blackness of American music curricula.

Shift priorities

The short version of my argument may be summarized grammatically: as a general migration from the definite article “the” to the indefinite article “a”. Whatever was “the” foundation for music and music education is now simply becoming “a” foundation.

Are Chorales by Johann Sebastian Bach “the” basis for studying harmony and music theory or just certainly one of many? And is Beethoven's Ninth Symphony “the” standard for such symphonies or simply “a” standard?

This grammatical shift has caused panic amongst conservative voices. But what happens in music simply reflects what happens in society as a complete, be it in science, politics, justice or popular culture.

For my part, I welcome rethinking our shared musical foundations and might consider no higher composer than Beethoven – and his fascinating Ninth Symphony – as a start line for creating recent musical foundations.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply