When you concentrate on the risks of climate change, the concept of abrupt changes is sort of frightening. Films like “The day after tomorrow“This fear is fueled by visions of unimaginable storms and people fleeing rapid temperature changes.”

While Hollywood clearly takes liberties with the speed and scale of disasters, several recent studies Alarm triggered in the true world that a vital ocean current that transports heat to northern countries could collapse inside this century, with potentially catastrophic consequences.

This scenario has occurred before, most recently greater than 16,000 years agoHowever, this requires that Greenland releases a whole lot of ice into the ocean.

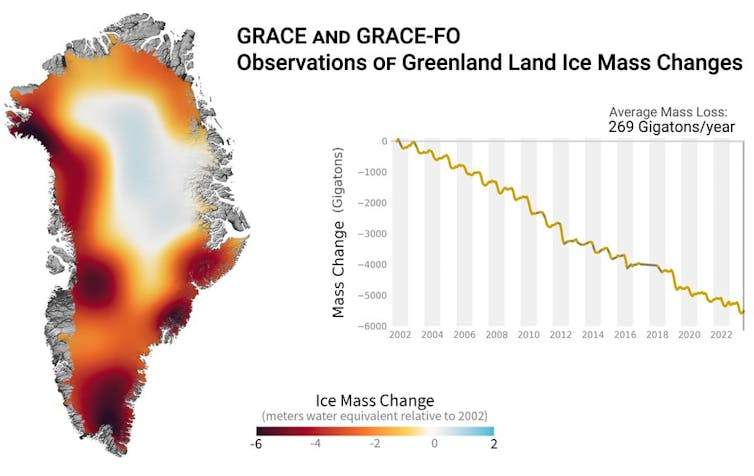

Our latest research, published within the journal Science, suggests that while Greenland is indeed currently losing huge and worrying amounts of ice, couldn’t last long enough to show off the ability itself. A better take a look at Evidence from the past shows why.

Blood and water

The Atlantic current system distributes heat and nutrients on a worldwide level, much like how the human circulatory system distributes heat and nutrients throughout the body.

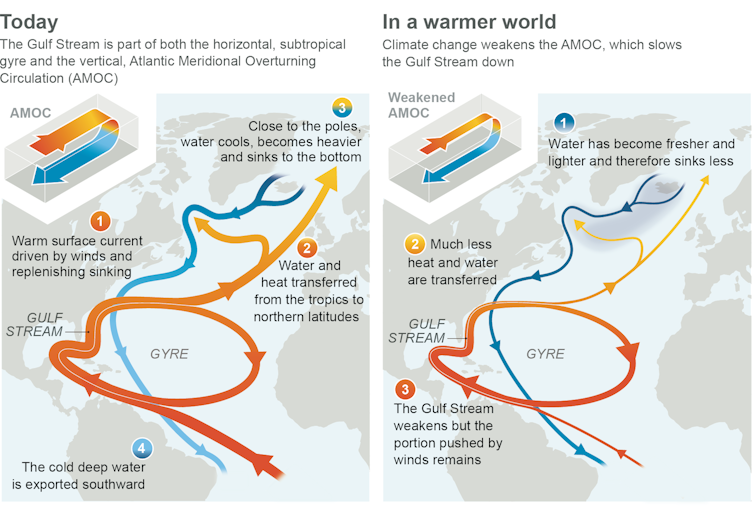

Warm water from the tropics circulates northward along the US Atlantic coast before crossing the Atlantic. As among the warm water evaporates and the surface water cools, becomes saltier and denserDenser water sinks, and this colder, denser water circulates southward again at depth. The fluctuations in temperature and salinity drive the pumping heart of the system.

A weakening of the Atlantic circulation may lead to global climate chaos.

Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC

Ice sheets are product of fresh water, so if icebergs enter the Atlantic quickly, it will possibly lower the ocean's salinity and slow its pumping heart. If surface water can now not sink to the depths and circulation breaks down, dramatic cooling would likely occur across Europe and North America. Both the Amazon rainforest and the Sahel of Africa would turn out to be drier, and the warming and melting of Antarctica would speed up – all inside years to a long time.

Today, Greenland's ice is melting rapidly, and a few scientists fear that the Atlantic current system could also be heading toward a climatic tipping point this century. But is that this concern justified?

To answer this query, we want to look back into the past.

A radioactive discovery

In the Eighties, a young scientist named Hartmut Heinrich and his colleagues collected a series of deep-sea sediment cores from the seafloor to analyze whether nuclear waste could possibly be safely buried within the depths of the North Atlantic.

Sediment cores contain a history of the whole lot that has accrued on that a part of the ocean floor. Hundreds of hundreds of yearsHeinrich found several layers with quite a few mineral grains and rock fragments from the land.

The sediment grains were too large to have been carried to the center of the ocean by wind or ocean currents alone. Heinrich realized that they brought there by icebergswhich had absorbed the rocks and minerals when the icebergs were still a part of the glaciers on land.

The layers with essentially the most rock and mineral stays, from a time when icebergs appeared in large numbers, coincided with a powerful weakening of the Atlantic current system. These periods at the moment are referred to as Heinrich events.

As Paleoclimate scientistwe use natural records similar to sediment cores to know the past. By measuring uranium isotopes within the sediments, we were capable of determine the deposition rate of sediments dropped by icebergs. The amount of debris allowed us to estimate how much freshwater These icebergs have caused additional damage to the oceans and we’re comparing the numbers with today to evaluate whether history could repeat itself within the near future.

Why a shutdown will not be likely anytime soon

So will the Atlantic current system be heading towards a climatic tipping point attributable to the melting of Greenland? We think that’s unlikely in the following few a long time.

Although Greenland is currently losing enormous amounts of ice—which is worrying and comparable to a medium-magnitude Heinrich event—the ice loss is unlikely to proceed long enough to stop the flow by itself.

Icebergs are rather more effective when the present is interrupted, as meltwater from the land, partly because icebergs can transport freshwater on to the places where the present sinks. However, future warming will cause the Greenland ice sheet retreat from the coast too early to deliver enough fresh water via iceberg.

NASA

The strength of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is A decline of 24 to 39% is anticipated by 2100. Until then, iceberg formation in Greenland shall be closer to the weakest Heinrich events of the past. Heinrich events, then again, lasted 200 years or so.

Rather than icebergs, meltwater flowing into the Atlantic from the island's edge is anticipated to be the essential explanation for Greenland's thinning. Meltwater still brings freshwater into the ocean, nevertheless it mixes with seawater and moves along the coast relatively than directly supplying freshwater to the open sea like drifting icebergs.

But that doesn’t mean that the flow will not be in danger

The future trajectory of the Atlantic current system is more likely to be determined by a mix of slowing but simpler icebergs and faster but less influential surface runoff. To make matters worse, rising ocean surface temperatures could slow the present even further.

The pumping heart of the Earth could still be at risk, but experience shows that the danger will not be as great as some fear.

In The Day After Tomorrow, a slowdown within the Atlantic current system froze New York City. Based on our research, we are able to take comfort within the incontrovertible fact that such a scenario is unlikely to occur in our lifetime. Nevertheless, vigorous efforts to mitigate climate change are still needed to make sure protection for future generations.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply