In In 1959, when Soviet Prime Minister Nikita Khrushchev visited San Francisco and members of the International Longshoreman's Union greeted him with cheers, with newspaperman Frank Coniff quipping: “This is the damnedest town. They cheer for Khrushchev and boo Willie Mays.”

It was the peak of the Cold War and for Coniff and lots of of his readers there was no higher symbol of America than Mays. At that point, Mays was a 28-year-old center fielder of the San Francisco Giants and the most effective baseball player on the planet, and he was occasionally booed by his own team's fans.

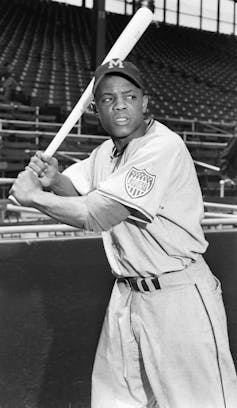

A decade earlier Mays played for the Birmingham Black Baronsa Negro League team near his hometown of Westfield, Alabama, while still in highschool.

Mays, who died on June 18, 2024 on the age of 93, was not only the best baseball player of the last 80 years and possibly of all time, but in addition an enormously essential figure in American sports, culture and history. His journey from the segregated Deep South of his childhood to being honored by President Barack Obama with the Presidential Medal of Freedom encompasses much of American racial history within the twentieth and early twenty first centuries.

In 2009, Mays traveled to the All-Star Game, where he a record of 24 times (from 1959-1962 there have been two All-Star games per 12 months), on Air Force One, where He told an enraptured and smiling President Obama how much it meant to him to see an African American elected president after his childhood in Birmingham.

Mays repeated several times how proud he was of Obama. The president responded: “If it weren't for people like you and Jackie (Robinson), I'm not sure I would have ever been elected to the White House.”

“Racism and racist swear words”

Mays began his profession in 1951 with the New York Giants4 years after Jackie Robinson played his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He became generally known as the “Say Hey Kid” due to his youth, exuberant playing style and his habit of greeting individuals with “Say Hey.”

Bettman/GettyImages

In these years, the mixing of the National and American Leagues was still in its early stages. There was an off-the-cuff rule Limiting the variety of non-white players per team to a maximum of three. Many teams, including the Yankees and the Red Sox, were still all-white.

Although the Giants played on the northern fringe of Harlem, where Mays lived early in his profession and was widely liked, Mays was subjected to the identical racism and racist abuse as Robinson in the course of the team's trips to southern cities and spring training in Florida.

The centrality of baseball in American culture on the time made Mays much more significant. At that point, baseball players were still by far essentially the most famous athletes within the United States, and far of the country watched the World Series every fall.

In the late FiftiesMays was, together with Mickey Mantle, America's most famous baseball player. For a long time, it has not been unusual for African-American athletes to be widely admired, but Mays was the primary. Mays' appeal to all fans was not only based on how good he was as a player, but in addition on the verve with which he played the sport. Excite fans with basket catches and daredevil baserunning, in addition to a public personality who was outgoing and friendly.

Representative … with “royal stature”

Robinson was a pioneering and unique figure in American history, but Mays's impact on the culture was broader and a minimum of as significant.

Frank GurdyProfessor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University, summed it up as follows: “Mays was this black mega-superstar in this country who somehow managed to transcend his background as someone from the Jim Crow South and become attractive to white America. He could be black and represent black participation in sports while maintaining a majestic stature that appealed to all people.”

(Bruce Bennett Studios/Getty Images)

In the Nineteen Sixties, when Mays was the most effective and most famous baseball player on the planet, he was criticized by some because they weren’t radical or open enoughThis criticism seems somewhat unfair today.

Unlike many other great African-American athletes of that point, comparable to Bill Russell, Tommie Smith, John Carlos, Wilt Chamberlain, Jim Brown or Robinson, Mays was a product of the South and carried that trauma with him to some extent.

It is commonly missed that within the last decade of his profession he was deeply respected respected by nearly all African-American baseball players for his skill and his role as an early trailblazer. As the longest-tenured player on the San Francisco Giants within the Nineteen Sixties, he set the tone and kept the peace in what was by far essentially the most diverse clubhouse in baseball on the time.

Daniel Shirey/MLB Photos via Getty Images

Because Mays played for the Giants in San Francisco from 1958 until he was transferred to the Metsand back to New York in the course of the 1972 season, his off-field activities didn’t all the time receive the eye they deserved. For a long time He worked with youth in San Francisco's Bayview-Hunters Point communitya predominantly African-American neighborhood that included Candlestick Park.

Overcoming racist history

Mays, who played his last game in the course of the 1973 World Serieswas a baseball star at the tip of the period when baseball was a vitally essential cultural institution and at a time when baseball was a pacesetter within the country in problems with civil rights and integration.

His exceptional statistical achievements speak for themselves, however the grace, joy, energy and intelligence with which he played the sport allowed him to face out from other great players of his – or any – era.

Mays' death shouldn’t be only a loss for baseball, but for all of America. Willie Mays is a reminder of what America can produce and that there remains to be hope that the country can put its ugly racial history behind it and embrace a graceful, talented and proud African American as a uniquely essential national hero.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply