The Jewish Passover commemorates the biblical story of the Israelites enslaved by Egypt and their miraculous escape. During a ritual festival often called a SederFamilies rejoice this ancient story of liberation and remind each latest generation to never take freedom as a right.

Every yr, a written guide called the Haggadah is read on the Seder table. The core text consists of an outline of formality foods, the story of the Exodus, blessings, commentaries, hymns and songs. The word Haggadah – “to tell” in Hebrew – is derived from Exodus 13:8a verse that instructed the Israelites to commemorate their deliverance and tell the story to their children.

Although the traditional festival that became Passover has been celebrated since biblical times, the entire text of the Haggadah arose only within the eighth to ninth centuries. And it wasn't until the 14th century that it was fully developed, lavishly lit versions was created, which was utilized by the Jewish communities in Germany, Italy and Spain. Medieval editors integrated decorative borderslike for instance fantastic, animal-like creatures borrowed from the broader culture.

This artistic freedom, in addition to minor changes to the text over time, resulted within the Haggadah becoming each a mirror and a commentary on the societies during which it was written. Here on the University of Florida's Price Library of Judaica, where I’m a curator and medieval Hebrew scholarWe have tons of of Haggadahs – every one a glimpse into the way in which Jews at a specific time and place adapted the narrative of the Passover story.

An illustrated classic

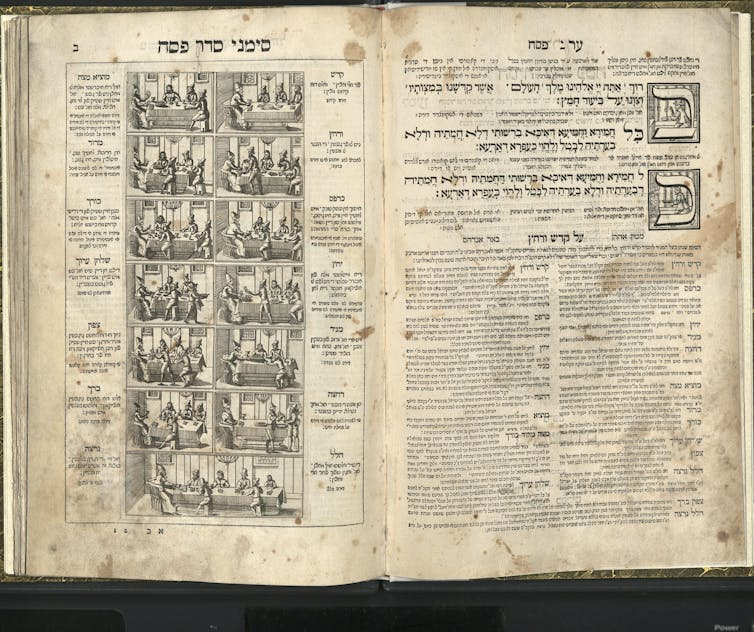

One of the best examples of this mixing of cultures in our library was printed in Amsterdam in 1695.

Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica, CC BY-ND

The Amsterdam Haggadah was illustrated by Abraham Bar Yaakov, a German pastor who converted to Judaism. Bar Yaakov eschewed the standard use of woodcut images and created a series of engravings based on Bible illustrations by the Swiss engraver Matthäus Merian the Elder. In addition, he added a pull-out map of the route of the Exodus and an imaginative depiction of the Temple in Jerusalem.

Bar Yaakov also added a picture of the “four sons” standing together — certainly one of the numerous elements of the Haggadah geared toward motivating and teaching children seated in the course of the long Seder meal. Each son represents a different type of childdescribed by her attitude toward Passover: sensible, wicked, quiet, and someone who doesn't even know the best way to ask questions on the vacation.

In medieval Haggadahs, the evil son was normally depicted as a fighter – the personification of evil European Jews who were repeatedly subjected to raids and violent expulsions. In Bar Yaakov's depiction, the evil son is a Roman soldier balancing precariously on one foot and looking out on the sensible son, portrayed as Hannibal, the Carthaginian general who ruled within the third century B.C. fought against Rome

The second edition of this Haggadah was printed in 1712 with additional engravings Solomon Proops, founding father of a renowned Dutch-Jewish printing company. The text, traditionally written in Hebrew and Aramaic, included instructions in Yiddish and Ladino, the on a regular basis languages of Jews in Europe. The Ladin translations were specifically geared toward Sephardic Jews who arrived within the Netherlands after the expulsion from Spain and Portugal as well Portuguese “converts”” Returning to Judaism after their ancestors were forced to convert to Catholicism.

The Amsterdam Haggadah proved incredibly influential on later versions, as its illustrations were copied into modern times.

A Haggadah for everybody

Haggadahs existed until the twentieth century adapted and translated to fulfill the needs of various Jewish communities all over the world, including different religious denominations – Reform, Conservative, Orthodox – or political, social and labor groups similar to Zionists or Socialists. The key theme of the Haggadah, freedom from oppression, was tailored to contemporary situations and viewpoints.

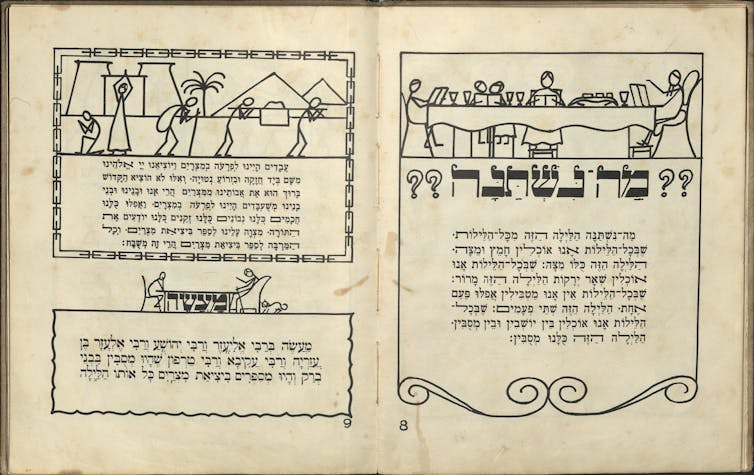

Modern Haggadah illustrations also reflected developments within the art world. There was a Jewish art teacher in Berlin within the Twenties Otto Geismarreinterpreted the story of the Exodus using easy black and white. modernist “stick figures”.” – one other Haggadah in our collection.

Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica, CC BY-ND

Despite their minimal lines, the figures are all expressive. Geismar even added elements of humor: a toddler sleeping on the table and in one other scene a family of stick figures have animated conversations and debates. In his depictions of ancient Israelite slaves, stick figures appear with heavy loads on their backs. He also divided the Hebrew text into more readable sections using eye-catching black and white decorative borders.

The striking simplicity of the design, which is aimed primarily at children, enjoyed great popularityand his work has been reprinted in several German and Dutch editions.

Wine – and occasional

There was a growing demand for various printed versions as Jews all over the world adapted the standard Haggadah. Meanwhile, some suppliers saw the chance to adapt it to their very own needs. Thus arose a phenomenon often called business haggadah: the product of clever corporations realizing the ability of promoting their wares in a book dedicated to the art of “storytelling.”

The most famous of those is the 1932 Maxwell House Haggadah, which was distributed free with every can of coffee purchased.

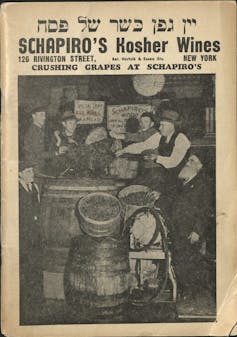

In 1938, the Schapiro House of Kosher Wines became known. The company, its flagship store on New York's Lower East Side, produced a Haggadah with an English translation and illustrations borrowed from the Amsterdam Haggadah. Owner Sam Schapiro cleverly linked his products to the Seder where participants drink 4 small cups of sacramental wine. Wine, considered a luxury item on the time, also symbolized freedom.

Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica, CC BY-ND

Just in case there have been doubts about alcohol promoting just five years after Prohibition The sacramental wine was difficult to accessSchapiro’s Haggadah advocated for the “health values” of wine. In two pages at the top of the book, the editor describes in English and Yiddish the supposed effectiveness of wine against a wide range of diseases, including typhus, depression, and even obesity.

Schapiro's Haggadah fulfilled the imperative of telling the story of the Exodus to a brand new generation – however the opening pages also offer a tribute in Yiddish Sam Schapiro's 40-year-old company. Here, Schapiro's is praised because the place where religious men and intellectuals alike could come together over a great glass of wine.

Commercial Haggadahs weren’t expected to grow to be venerable family heirlooms. Rather, they offered lower-income Jewish families a practical and reasonably priced option to take part in the annual ritual of liberation from bondage—one other expression of freedom.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply