Thousands of Republicans, from presidential candidates to grassroots party members, began assembling in Milwaukee on July 15, 2024, for the political ritual that takes place every 4 years, the party congress. Curators for political history of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History were there too. They describe themselves as “scavengers” of the physical objects that make up the story of political campaigns, from candidate buttons to signs, banners and the rest that matches in. the Smithsonian Campaign Collection – which dates back to George Washington – to “make sense of our moment for people who are wondering what we were all thinking,” as curator Jon Grinspan put it. Grinspan was joined by curators Claire Jerry and Lisa Kathleen Graddy in an interview with The Conversation's politics editor Naomi Schalit. They will update Conversation readers on their progress throughout the session.

Schalit: What do curators of political history do?

Lisa Kathleen Graddy: We attempt to document, through material culture, the connection Americans have with their democracy, with their government, how they’re affected by it, how they act on it, how they interact with it. Material culture includes all of the ephemeral things and products that individuals make and use to precise their opinions about politics.

Claire Jerry: We exit into the sphere to look at people working and interacting with these objects in real time. But we also wish to put it in a historical context. Of course, none of us could have watched anyone do it in 1860 or 1896, but by watching how people do it today, we will return and reinterpret the objects we collected previously.

Jon Grinspan: We're trying to elucidate the past to the current and the current to the longer term. We're attempting to draw on our really broad, deep history of democracy to make sense of the current.

Schalit: What items are notable in your collection?

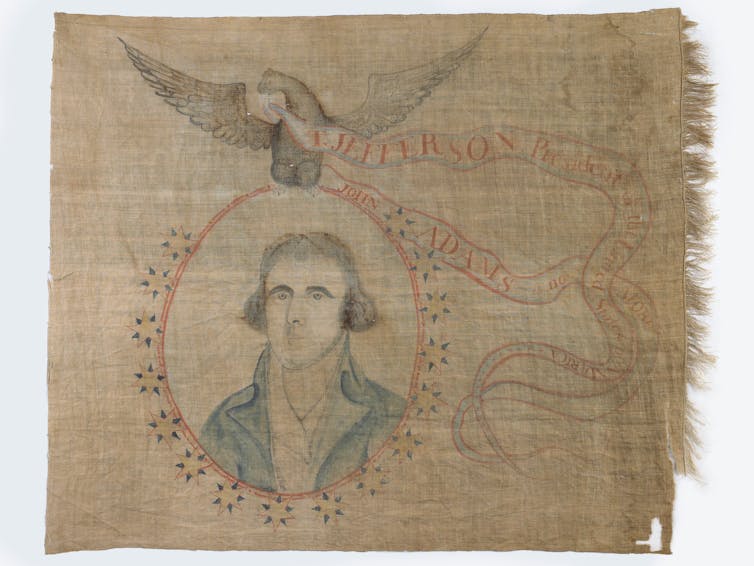

Grady: One of my favorite objects is a banner from Thomas Jefferson's inauguration in 1801It contains a portrait of Thomas Jefferson and an eagle holding one in all two ribbons above his head. The ribbons read: “T. Jefferson, President of the United States, John Adams is no more.”

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

The election of 1800 was an unsightly, bitter election that tore apart two friends – Jefferson and Adams – and pitted parties against one another. But it was also one in all those moments after we knew democracy would work. The losing side went, the winning side got here, and the reply was: we'll see you in 4 years and take a look at again. That's one in all the things that jogs my memory that we've been in bad situations before and we've gotten through them.

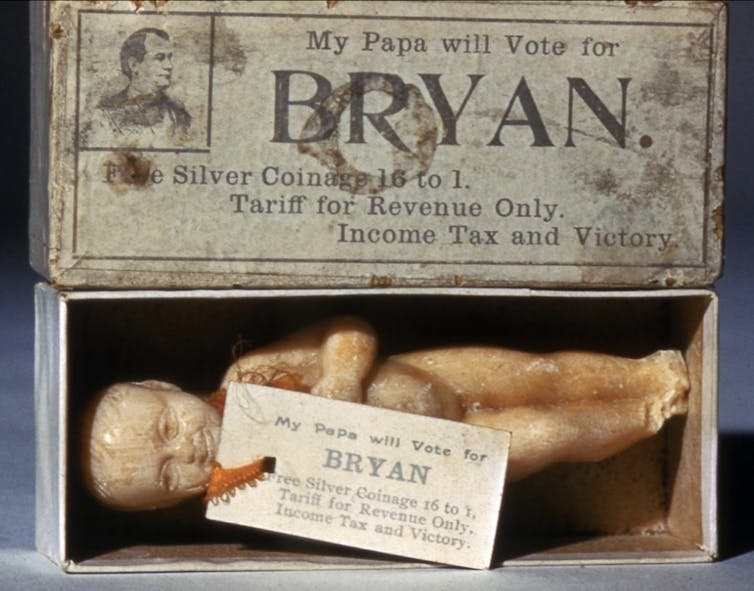

Jerry: I often follow Lisa Kathleen as she tells this beautiful story and warms everyone's heart by telling stories concerning the more ridiculous and silly things that occur in campaigns. And one in all my favorite objects within the museum are the soap babies from 1896.

They are 4 inch long babies molded from soap produced by soap manufacturers to advertise each William McKinley, the Republican candidate, and William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic candidate. They got here in little boxes with labels that said, “My father is for free silver! My father will vote for the gold standard!” Because, after all, nothing says economics higher than a four-inch naked baby manufactured from soap. They had nothing to do with economics, after all. Voters apparently hated them because they thought they looked too very like babies in coffins.

Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Ralph E. Becker Collection of Political Americana

But I prefer to speak about it because I prefer to speak about how technology has influenced what we collect over time and what we use in campaigns. This was about soap makers saying, “Look at the new, cool things we can make out of soap.”

Grinspan: We have two blue umbrellas. One is a more understated Nineteen Fifties umbrella from Dwight Eisenhower's campaign that has “I like Ike” written throughout it. And we’ve got a blue umbrella from the 2016 campaign that was utilized by Bernie Sanders protesters outside the Democratic National Convention. Sanders' name is scrawled throughout it. The writing alone is basically loud. And even if you happen to can't read, even if you happen to don't know who Eisenhower and Sanders are, these objects let you know something materially about their era.

Schalit: What will you be in search of on the congress?

Grinspan: Of course we search for material a few former president running for a second term, concerning the relationship between the campaign and the party, and between the party and grassroots or anonymous campaigners. But I actually don't think it's an excellent idea to go in with a checklist. A number of collecting is spontaneous. You see an object that just captures a moment, or expresses something really striking, or speaks to other objects in your collection in an ineffable or indescribable way.

Schalit: How do you go about collecting if you find yourself at one in all these events?

Grady: We search for looters. We comb the place and pick up things, from signs which might be lying there to signs that they're handing out. But we're also, um, extremely polite. I don't wish to say we're stalkers, but we watch people. We spot what seems to interest us and really nicely walk as much as them with a handshake and a business card and say, “Hi, I'm Lisa Kathleen Graddy. I'm a curator at the Smithsonian Institution. I really like your hat. Would you like to talk about maybe becoming part of the national narrative at the museum on the Mall?”

Schalit: What was the craziest thing you took home from a political event?

Grady: Convention standards, the large pillar-like signs which have the name of the state on them, are highly regarded souvenirs. Convention organizers assume they may wander away throughout the convention, and so they have more of them. We often attempt to get the usual of the candidate's state. We were very lucky that we couldn't get the New York standard on the 2016 Republican Convention, but Jon and I talked to the Indiana and Colorado delegations, who decided to maintain their standard and put it aside for us.

On the last night of the convention, all of the delegations signed them and Jon and I left the convention with two standards. They got just a little heavy on the strategy to our automotive, so we actually got in a pedicab. Somewhere on the earth there are mobile phone photos of us sitting in a pedicab with these two delegation standards, driving down the streets in Cleveland.

Schalit: Claire, you lately attended the Libertarian Movement Congress. What was your experience there?

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Jerry: The Libertarian convention felt more like a historic convention within the sense that there isn’t a candidate yet and so they are usually not running as a team, but there are separate groups of candidates for vp and president. All of those candidates have tables in a vendor area with buttons and flyers and books they've written and lanyards, all of which I took. One of the things we do is we take whatever is out there for everybody who attends the convention.

I assumed it was interesting to see that the Libertarians have an official symbol, which is a really elegant torch. But in addition they have an animal. We are all used to red, white and blue elephants and donkeys. I used to be less used to yellow and gold porcupines, the symbol of the Libertarians. It was quite a lot of fun to see people wearing porcupine-themed clothing and handing out porcupine buttons.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply