Many observers imagine that a controversial decision by the US Supreme Court on July 1, 2024, makes presidents kings – but they underestimate how radical the ruling could actually be. In fact, although the vast majority of the court said it was a tribute to the constitutional traditionSomething completely latest seems to have emerged: a legal tyrant, someone who’s above the law, a privilege that not even kings enjoyed.

Specifically, the court ruled that Presidents of the United States “a certain immunity for official acts” during their term of office and absolute immunity for acts that affect their “core competencies.” Legal scholars are still to seek out out what exactly which means And what may very well be considered an official act.

But criticism got here immediately. Judge Sonia Sotomayor disagreeddeclared: “In every exercise of official power, the President today stands as king above the law.”

But when Historians of medieval powerI do know that Sotomayor's argument will not be entirely correct. Kings were never above the law. Even the epitome of absolute monarchy, Louis XIV of France, who reigned from 1643 to 1715was not above the law. He embodied the law. Known because the “Sun King,” the law flowed through him and spread like rays of sunshine across his kingdom. He couldn’t break the law, for he was the law.

Étienne Colaud/National Library of France via Wikimedia Commons

A narrow distinction

This line between being above the law and really embodying the law is admittedly thin. One of the primary European thinkers to try to clarify this difference precisely was an excellent Twelfth-century politician named John of Salisbury.

John wrote that a king “a law unto itself”, but at the identical time he’s “a servant of the law”.

According to John, a king would at all times instinctively put the welfare of your entire community above his own private desires. If he did otherwise, he ceased to be a king and have become a tyrant. Confusingly, for John, tyrants weren’t entirely illegal: God sometimes used tyrants to punish an unjust people.

How to deal legally with a tyrannical king remained an almost insoluble problem.

A concrete solution

John of Salisbury's discussion of those questions remained at an abstract level. But only a couple of years after his death in 1180, his theoretical writings became real political concerns in England. The erratic King John, who reigned from 1199 to 1216flirted with tyrannical behavior.

Specifically, he imposed fines on people for the alleged crime of constructing him offended. There was nothing illegal about these fines. They were called “Amercings” – literally: You paid the king money for his mercy in order that he would stop being offended with you. However, John's practice was so erratic and so obviously cruel that his barons revolted and threatened to overthrow him in favor of a prince from France.

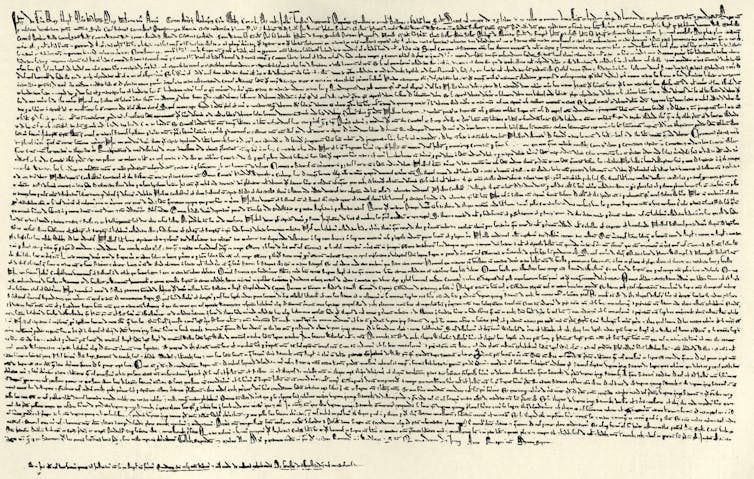

In order to pacify the empire, King John and the barons negotiated the famous Magna Cartawhich was long considered a central document of the Western legal tradition, and cited, for instance, in greater than 170 Supreme Court decisions.

In Magna Carta, John accepted the barons' demands that he regulate and limit the same old fines and other punitive measures. To be certain that he would keep his guarantees, Magna Carta also established a council of 25 barons to tell him when he had exceeded his legal authority. If the king didn’t follow their advice, “the whole community of the country” was empowered “harass and harass” by attacking his castles and possessions and making his life difficult.

The king had never been above the law and now this concept was enshrined in law.

Culture Club via Getty Images

A transition to democracy

Although Magna Carta was never fully implemented, it nevertheless modified the culture of the English monarchy.

If John had not died in 1216 during one other war together with his baronshe would probably have been overthrown. His son Henry III barely survived a serious rebellion during his reign. In 1326 an offended Parliament and Baron deposed Henry III's grandson Edward IIwho died in prison in 1327.

At the tip of the 14th century, the barons and Parliament overthrew Richard II.who also died in prison. Kings were never above the law and located themselves increasingly constrained by laws and parliamentary practices.

By the time of the American Revolution, the English kings had already ceded all significant authority to Parliament. When Thomas Jefferson railed against George III within the Declaration of Independence.He used the monarch as a logo for the English government basically.

“A prince whose character is marked by every act that constitutes a tyrant is not fit to be the ruler of a free people.” Jefferson wrote in 1776Despite the historical distance and legal differences, John of Salisbury couldn’t have put it higher.

Unlike – or so it seems – later US presidents, kings were never immune from the law. In their official actions and the exercise of their core powers, they were at all times defined and limited by legal precedents.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply