Stone Coubertin, Founder of the fashionable Olympic Gamesall the time saw the games as far more than the sum of their parts. “Olympism,” as he called it, was a brand new type of religion – a faith without gods, but which was nevertheless transcendent.

For Coubertin, preparing an athlete’s body and mind for peak performance in competition was a path to the “realization of perfection.” And if the competition were nation against world, happening every 4 years in numerous host cities, individual interests could be subordinated to national pride and global synergy. Coubertin described this sport as “in the service of global harmony” – nothing lower than a brand new “sports religion”.“ or “Religion of Athletics”.

Only twenty years after the fashionable revival of the games In 1896, Europe was torn apart by World War I, making the risks of national rivalries all too clear. And as Coubertin, a French baron and pacifist, wrote: “unbridled competition even creates an atmosphere of jealousy, envy, vanity and mistrust.”

He was convinced, nonetheless, that these base instincts might be curbed by a “grandiose and powerful” “regulator.” Expressed through Olympismthe faith of athletics could regulate sport and national pride in a way that will bring about world harmony in a single place every 4 years – a goal that will not be attainable through politics or sectarian religion.

But the Games haven’t been wanting challenges over the past 100 years. As researchers studying religion and sportwe ask ourselves whether Coubertin’s noble ideal of the “Religio athletae” still applies – if it ever did.

Ancient inspiration

Coubertin's desire to revive the Olympic Games after 1,500 years of peace was prompted by his concerns about challenges and changes within the early twentieth centuryFor example, he believed that industrialization weakened young men physically and morally.

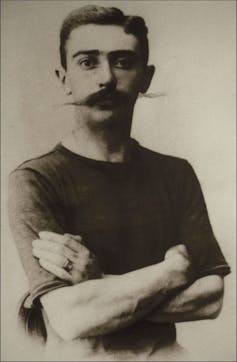

Francois Lochon/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

However, as science became more powerful, traditional religion was seen less and fewer as a panacea for the world's ills. A brand new world was dawning and Coubertin hoped that Olympism would act as a corrective. Coubertin had been a fairly obsessive follower of ancient Greece since childhood and saw in the traditional games elements that, if modernized, could offer unique answers to among the great problems of his time.

In particular, he looked back on the ancient Greek ideal the harmony of mind and body, which the participants expressed every 4 years within the Greek city of Olympia, the sanctuary of Zeus. The games were open to Greek men – Women and slaves weren’t allowed to participate – and the fights might be brutally violent.

By making this ideal the premise of contemporary games, Coubertin hoped to present them a way of Balance, proportion and aweThe Olympic Games brought the magic of ancient Greece into the twentieth century – symbolized to at the present time by the torch relay from Olympia to the opening ceremony.

Not all of his views on the traditional games were glowing. Coubertin also believed that they were “chaotic”, “impractical and annoying”, and susceptible to excess and corruption. He feared that the fashionable Olympic Games could end in the same way.

AP Photo/Thanasis Stavrakis, File

At the identical time, he was convinced that the spirit of the games might be a “regulator” of the type of excessive behavior that sport can result in. In ancient Olympia Coubertin wrote“vulgar competition was transformed and in a sense sanctified” out of respect for the body and mind, which work toward the perfection represented by the gods.

The games today

The International Olympic Committee repeated Coubertin's Desire to create unity and peace through athletics. Current IOC President Thomas Bach said: “The common goal of the UN and the IOC is to make the world a better and more peaceful place“For the IOC, this means putting sport at the service of the peaceful development of humanity.”

Pascal Le Segretain/Pool photo via AP

In fact, it is nearly not possible to assume any event apart from sport by which so many countries from all around the world come together and compete under the identical rules and without the specter of violence.

Every two years Billions of individuals experience this surge of national and global pride, five interlocking, multi-colored Olympic rings And although the Greek gods – or any god for that matter – don’t appear, a type of civil religion nevertheless connects athletes and spectators to the “global community” that the Olympic Games are intended to create.

What Coubertin couldn’t have foreseen was the role that cash and politics would play – and he recalled the “vulgar competition” that he believed had undermined the traditional Games. Cities vying to host the Olympic Games often start Projects that harm the environment and the local neighborhoodand the countries were accused of “Sportswear”: using the feel-good promoting of sport to distract from a deplorable human rights record. For example, the Nazi government famously used the Olympic Games 1936 in Berlin as a first-rate example of his racial theory of the ethnic superiority of the Germans.

In other words, the Olympic Games were a vehicle for each unethical behavior and international antagonism – a transparent violation of Coubertin’s vision.

Perhaps Olympism was all the time a pipe dream; perhaps sport never had the facility to create and sustain a “religio athletae.” We would argue that the episodic rise of healthy National pride and largely unknown amateur athletes are still a reason to admire the Olympics. But it’s unclear how what is sweet concerning the Games can produce an inspiring recent “regulator” beyond individual performance and national medal counts – or if that’s even possible.

image credit : theconversation.com

Leave a Reply